December 30, 2022

BEIJING – Editor’s note: China is home to 56 UNESCO World Heritage sites. To find out how these natural and cultural gems still shine and continue to inspire the nation in this new era of development, China Daily is running a series of reports covering 10 groups of selected sites from across the country. In this installment, we visit the southern part of Anhui province to explore a world above the clouds and traditions steeped in history.

A “monkey” squats on his haunches, looking into the distance from the mountaintop.

Time goes by silently and he will not be hurried. He can glance upon what is happening in Taiping town — the name means “peace and tranquility” in Chinese.

He observes, unmoved, clouds rolling in and away, seeming to mirror the tumult of the sea below.

The stone monkey, actually a rock in the shape of a primate, has been surveying his domain since time immemorial. It could be measured in millennia but that would almost seem too short a time span.

It is one of the most famous rock formations on the Huangshan Mountain, also known as the Yellow Mountain, in East China’s Anhui province. People call it the “Monkey Watching the Sea”.

For thousands of years, the Chinese have been fascinated by these vivid rock formations that seem to spark the imagination into action: “Mr Immortal Showing the Way”, “Blossom at Ink Brush Tip”, and “Dragon-head Fish Carrying the Golden Turtle” are just some of the colorful descriptions.

Nature shaped them, as if to play with human sensitivities.

And this gives Huangshan Mountain a unique charm: It makes you feel the unity of man and nature, offering a fresh perspective, no matter how many times you’ve been there.

Huangshan Mountain is inscribed on both UNESCO’s world cultural and natural heritage lists. It is a UNESCO Global Geopark characterized by its Mesozoic granite landscape.

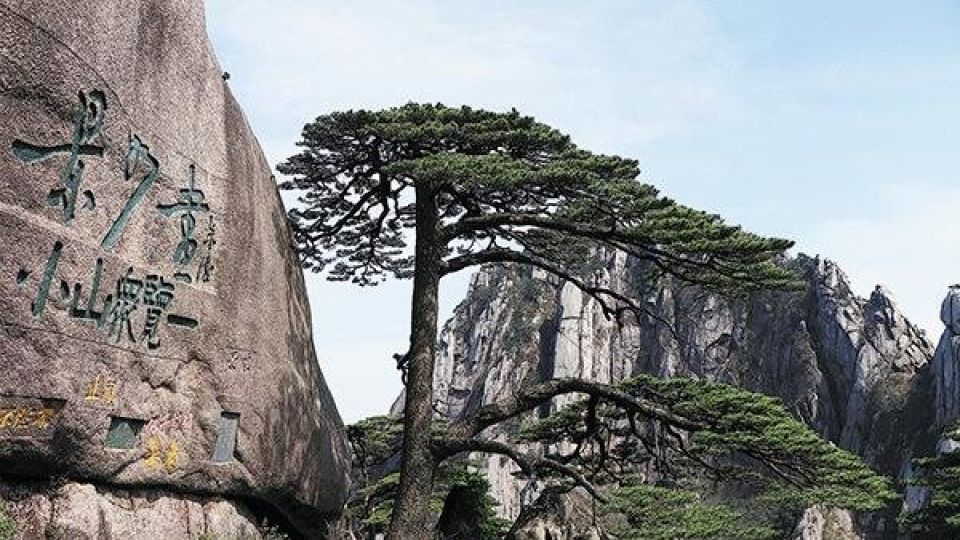

Huangshan Mountain in Anhui province is known for its imposing peaks, massive granitic boulders and ancient pine trees.(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

It has numerous imposing peaks, massive granitic boulders and ancient pine trees. Growing from cracks in the rocks, some of the pine trees are gnarled, while some stand sentinel, with an umbrella-like canopy remaining green throughout the year. In winter and spring, frost crowns the pine needles, turning the view into a wonderland.

There are also waterfalls, lakes and hot springs.

Hundreds of kilometers away from the coast, the Huangshan Mountain scenic area is divided into five sections named after hai (sea) according to their location, because of an iconic sea of clouds, each of which displays different characteristics — heavy, tranquil, wreathed in mist and churning.

In 2006, former researcher at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences Pu Qingyu, now in his 80s, joined a research program into Huangshan’s granite geomorphic landscape for six years.

According to their research findings, the granitic pluton of Huangshan dates back around 120 million years, but the imposing peaks and deep valleys were gradually formed around a million years ago, eroded by wind, rain, gravity disintegration and glaciation. However, there remains debate over the latter.

Pu explains in a documentary featuring Huangshan that the granite outcroppings on the mountain cover more than 70 percent of its area, forming the main body of its rock landscape.

The Qianhai (Front Sea) and Nanhai (South Sea) sections have tall and majestic bodies, while the peaks at the Beihai (North Sea) section are steep and more exquisite. Xihai (West Sea) is a precipitous, magnificent canyon.

There’s a saying that claims Huangshan exhausts people’s expectations of a mountain. Through the ages, it’s a special place for hermits, monks, poets and painters, who have left behind voluminous art and literary works about the mountain.

Among them were Hongren (1610-63), Mei Qing (1623-97) and Shitao (1642-1708), the three representatives of the “Huangshan school of painting”.

The three ink painters of the late Ming (1368-1644) and early Qing (1644-1911) dynasties devoted most of their artistic life to the mountain and, in return, the mountain made them who they were.

Mei said that since his visit to Huangshan, most of his strokes were about the mountain. Shitao said: “Huangshan is my teacher, and I’m a friend to Huangshan.”

Wang Tao, director of Huangshan city’s calligraphy and painting academy, says that Hongren’s work presented the static, austere side of the mountain by showing its “muscles and bones” with clear lines, whereas Mei depicted its unpredictable, illusory motions, and Shitao’s drawings conveyed a sense of ease.

According to Wang, Hongren sketched Huangshan Mountain for what it was, rather than picturing it with established impression of a mountain that bore a projection of human emotions.

Huangshan Mountain in southern Anhui province, a World Heritage Site, is known for its breathtaking landscape and rich culture. (PHOTO BY SHI YALEI / CHINA DAILY)

“Hongren found his own ink language and expression in nature. He had to put all his heart and soul into this topic and keep exploring it so that he could achieve such things,” Wang says.

He was constantly inspired by his predecessors over the previous four decades, from their solid painting methods to their general attitude toward art and life. He centers on portraying the ancient villages around Huangshan and frequently sketches on site to observe life there, endeavoring to convey the ideal, idyllic homeland in his mind.

Huangshan’s kaleidoscope also provides infinite materials for the camera. It mobilizes photographers to get up early and stay up late, equipment slung over their shoulders, climbing, racing against time, or waiting, simply to catch a decisive moment.

Local photographer Shi Yalei, 31, tackles Huangshan Mountain some 20 times a year. Nowadays, livestreaming programs enable people to follow the conditions at the top instantaneously, so if something attracts him, he sets out immediately.

His father, also a shutterbug, led him on this pilgrimage over a decade ago and influenced his initial framing of the stones and clouds.

Shi says, his father focused on presenting an impressionistic picture of the peaks and pine forests to show the mountain’s grand momentum — like a Chinese landscape painting — while he, himself, prefers to capture the light and shade of smaller views.

Huangshan Mountain in southern Anhui province, a World Heritage Site, is known for its breathtaking landscape and rich culture. (PHOTO BY SHI YALEI / CHINA DAILY)

In spring, he observes the sprouting of pine needles. In summer, the mountain is stunningly verdant. The morning and sunset glows are the most impressive in fall, and he likes snowy days the most. He also sees stump-tailed macaques stopping along the way from time to time.

“On top of the mountain, it’s like you travel through years in the blink of an eye,” Shi says.

Shi’s father passed away two years ago. Sometimes he feels the pause of time on Huangshan. It reminds him of the days when the two of them would take the earliest cable car onto the mountain and wait at Shixin Peak for several hours for the mist and clouds to clear away, or huddling on the top in — 30 C to shoot the frost.

He thinks he has taken on the mantle of his father, although he jokes he’s not as devoted as his old man.

“Well, at least, I’m no longer fooling around and I am taking it seriously, which is what my father would have wanted,” Shi says.

Wang Kaihao and Zhu Lixin contributed to this story.