July 27, 2023

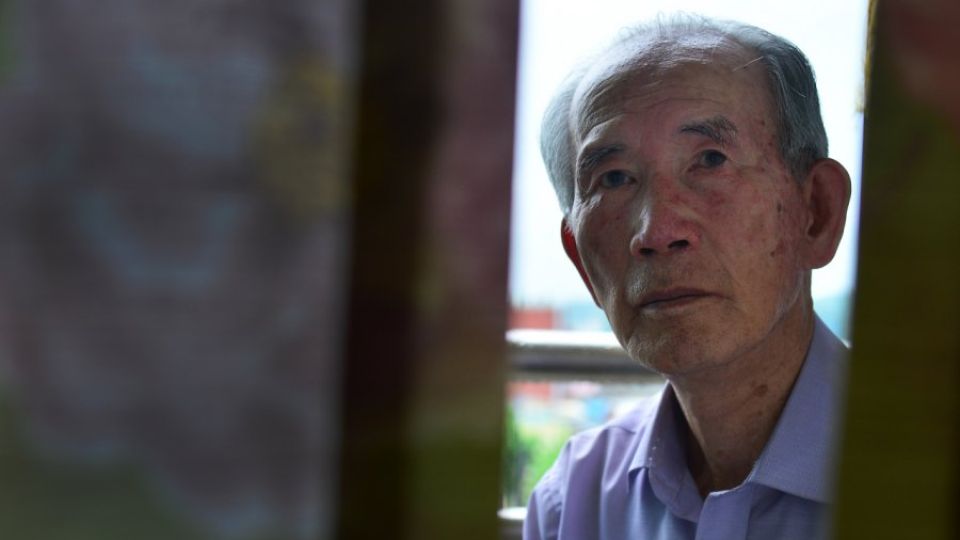

ICHEON, Gyeonggi Province – Yoo Young-bok, 93, recalls when he, then a 23-year-old South Korean rifle soldier, was captured by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army during the Geumhwa area battle, in Gangwon Province in June 1953, a month before the Armistice Agreement was signed to cease the Korean War.

Upon his capture, he was sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Sungho-ri, Kangdong County, South Pyongan Province, the following month. Little did he know at that moment that he would become a POW that nobody would want for an astonishing 47 years.

Despite 70 years having elapsed since the signing of the armistice on July 27, 1953, there are still South Korean POWs who remain in captivity, as recounted by Yoo, who managed to escape North Korea by himself in 2000 at age 70. Other POWs would also hold onto hope, yearning for the day when their country would bring them home.

“So day after day, I kept enduring, clinging to a glimmer of hope, praying for change to grace my life. But in the end, change never arrived, and time just kept passing by,” Yoo said in an interview with The Korea Herald at his home in Icheon, Gyeonggi Province.

In North Korea, the war veteran was subjected to forced hard labor in mines for 37 years.

Yoo endured grueling and harsh conditions while working at a monazite mine in Cholsan County, North Pyongan Province, and later at the Komdok and Tongam mines in South Hamgyong Province. The relentless labor in the mines led to him contracting pulmonary tuberculosis.

During his time in North Korea, Yoo did not receive any payment for the first three years and two months of his forced labor. Afterward, he was provided with a minimum salary that barely allowed him to scrape by and make a living.

At 60, he quit his mining job, which had left his body weak and frail. But he was not better off, having to face hunger with no money, particularly during the deadly famine period of the 1990s.

As a South Korean POW, Yoo said he faced social disadvantages in the North.

“In North Korean society, one’s social standing is evaluated based on their family background and the accomplishments of one’s grandfather and father, as well as their own achievements,” Yoo explained.

“South Korean prisoners of war who pointed guns at North Koreans are deemed to be part of the most malevolent group.”

Children of South Korean POWs were also denied meaningful social advancement. They were not allowed to join the military and had no opportunity to become members of the ruling party.

The destinies of numerous POWs who fought for South Korea’s freedom against communist adversaries during the 1950-53 Korean War were marked by tragedy in North Korea. While some were assimilated into the North Korean military, others were forced to endure decades of hard labor in mines and various locations, subjected to perilous and grueling conditions until they died or were unable to continue working due to old age.

Such treatment of POWs in North Korea is a clear violation of the Geneva Conventions, which state that POWs must always be treated humanely in all circumstances and protected against any act of violence and mistreatment.

93-year-old Yoo Young-bok speaks to The Korea Herald in the city of Icheon, Gyeonggi Province in July 2023. (Photo – Ji Da-gyum/The Korea Herald)

But in the oppressive shadows of North Korea, defying authority meant facing dire consequences. As a result, POWs had no choice but to endure, counting the agonizing moments, and yearning for an opportunity and the support of the South Korean government finally to return home and reunite with their loved ones.

“Those who resist the authorities in North Korea not only endure beatings but also vanish overnight, leaving their fate unknown to everyone,” Yoo said.

“So, many people opted to feign compliance, patiently waiting for the right moment. They endured these hardships with the hope that over time, inter-Korean relations would improve one day.”

Yoo personally had to relinquish the hopes of repatriation he had clung to for over four decades. He was determined to defect to South Korea, even though it meant risking his life, amidst the fervent atmosphere that enveloped the Korean Peninsula in the wake of the historic first inter-Korean summit in June 2000.

“I had hoped that President Kim Dae-jung would make an appeal to Kim Jong-il, allowing elderly prisoners of war like myself, who longed to return to our hometowns after being manipulated for such a long time by North Korea until the age of 60. We were discarded items as if we were just objects,” Yoo said.

“But when the South Korean president came, there were no words spoken on our behalf, and I came to realize that I couldn’t rely on anyone else for my salvation,” he said.

Yoo escaped from North Korea on July 27, 2000 by crossing the Tumen River and eventually made it to South Korea on Aug. 30 of that year.

“I knew that getting caught could mean death,” Yoo said. “But if fate was on my side, I believed I could safely make it through.”

Yoo Young-bok held a belated retirement ceremony at the 5th Infantry Division headquarters located in Yeoncheon County, Gangwon Province, near the inter-Korean border in October 2000. (Courtesy of Yoo)

After arriving in South Korea, he became aware of the large number of South Korean soldiers who had disappeared during the Korean War. He also learned about the general lack of awareness among people regarding the reality of POWs.

Yoo faced probing questions, including accusations that he might have been a spy dispatched by the North Korean regime.

“The responsibility to testify and speak on behalf of those who were detained as prisoners of war in North Korea, shedding light on the duration of their detention, the reasons behind it, and the conditions they endured, is a burden that I felt upon returning from North Korea,” Yoo said.

“Those who have been left behind in North Korea cannot fulfill this role.”

Between 1994 and 2010, a total of 80 POWs detained in North Korea defected to South Korea. As of July, only 13 of them are still alive, with an average age of 93 or 94, according to Mulmangcho, a civic group supporting defected POWs. Under the Kim Jong-un regime, no prisoner of war has managed to reach South Korea.

None of these elderly individuals are able to move freely, and only around five of them can move with assistance.

North Korean forces turn over prisoners of war to the UN authorities at the POW receiving center at Panmunjom on the inter-Korean border in the process of repatriation. (Date unknown, US Air Force)

Yoo is considered somewhat luckier compared to the countless other POWs whom North Korea has refused to repatriate, despite the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement.

The agreement clearly stipulates the release and repatriation of all POWs held by each side, but unfortunately, many South Korean POWs remain in North Korean custody, their fates unresolved.

During the Korean War, approximately 82,000 South Korean soldiers were estimated to be missing in action, according to the UN forces. However, only a final count of 8,343 South Korean POWs were repatriated from April 1953 to January 1954.

The significant discrepancy suggests that a substantial number of South Korean POWs were likely forcibly detained in North Korea. At least 50,000 POWs from South Korea were not repatriated, according to the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in North Korea.

But North Korea has never officially recognized the existence of POWs, except for the ones who were repatriated.

On the contrary, the South Korean and UN forces followed the principle of respecting the free will of POWs and repatriated all North Korean and Chinese POWs who wished to return. A total of 75,823 North Korean POWs were sent home.

“The repatriation of prisoners of war has been unfair,” Yoo lamented.

“Exchanges should adhere to the principle of reciprocity, but there is a significant disparity in the number of prisoners of war repatriated from South and North Korea.”

South Korea has failed to bring home any additional POWs from North Korea.

Portraits of Joseph Stalin and North Korean leader Kim II-sung can be seen near where UN troops are under fire. (Date unknown, US Department of Defense)

governments, even during the three inter-Korean summits held between 2000 and 2018, with no mention of the thorny issue in the joint statements from the summits.

Now 23 long years since his escape to South Korea, Yoo’s face bears a weary and disheartened expression. His heart weighs heavy, he said, with the disappointment of unfulfilled hopes for significant change over the years.

“Now, the problem has persisted for too long, and I find myself questioning what can be resolved at this point? Sadly, the majority of the South Korean prisoners of war have already passed away, and North Korea persists in making false claims,” Yoo said.

“Prisoners of war always carry deep-seated resentment. So at the very least, we should document these experiences in history, so we can preserve them and potentially use them if there arises an opportunity in the future for North Korea to offer an apology,” he said.

Despite North Korea’s refusal, Yoo said the South Korean government should continue to persevere in its efforts to bring POWs home.

“Why should the country bring back elderly soldiers who were prisoners of war? What’s the importance of doing so? Some might ask this,” Yoo said.

Bringing back elderly soldiers who were POWs holds significant importance in recognizing their contributions to fighting for their country’s freedom and motivating future generations to serve their country with dedication and pride.

If the country fails to demonstrate accountability and care for its veterans, it may deter others from willingly stepping up to serve in times of war, he said. Given that the Korean Peninsula is still technically at war, it is critical to address the issue.

“If the country doesn’t take responsibility for prisoners of war, who will be willing to go to the front line if war breaks out?” Yoo asked.

“We have to remember that the Korean War is not yet over.”