August 22, 2024

DHAKA – One does not need to remember Rabindranath on the occasion of the anniversary of his death—22 Srabon or August 7 to be precise. Rabindranath is evoked often, and with spontaneity in our everyday lives. But perhaps he is recalled with a particular kind of urgency when we experience turmoil of the kind we are experiencing at our present political juncture. In his long life, Rabindranath confronted protests and movements, revolutions and resistance efforts. His lectures, essays, letters, novels, and songs often tell the tales of those struggles. From the Swadeshi Movement to Bongo Bhongo to colonial violence against the unarmed, Rabindranath’s pen addressed them all. On the occasion of this baishe srabon, here are six essential revolutionary Rabindranath pieces everyone should read.

Letter to Lord Chelmsford Rejecting Knighthood (29 May, 1919)

Rabindranath was awarded the Knighthood in 1915, after winning the Nobel prize for Gitanjali (1910). However, he returned his Knighthood in 1919 in protest of Brigadier General Dyer’s killings of 379 innocent, unarmed civilians at Amritsar in the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre.

Condemning the killing of unarmed civilians, Rabindranath wrote to the Viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford: “Considering that such treatment has been meted out to a population, disarmed and resourceless, by a power which has the most terribly efficient organisation for destruction of human lives, we must strongly assert that it can claim no political expediency, far less moral justification.” He adds, “The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.”

A bold declaration of solidarity and a firm rejection of such brutal violence meted out against unarmed general people, the letter affirms Rabindranath’s sense of what is just and what one must stand for.

Manusher Dhormo (1931)

A compilation of lectures delivered by Rabindranath and drawn from his Hibbert Lectures given at Oxford University in 1930, Manusher Dhormo is essential for everyone who wants to familiarise themselves with Rabindranath’s philosophy on life and being human. The lectures were delivered while tensions surrounding India’s independence struggle were high. Rabindranath proposes that the future of humanity must be based upon equality among the races when he claims, “I ask them to claim the right of manhood to be friends of men, and not the right of a particular proud race or nation which may boast of the fatal quality of being the rulers of men.” A critique of race egotism and the race-centric human order, the book attests to Rabindranth’s belief in the notions of insubordination, creativity, and autonomy.

Pother Sonchoy (1939)

Rabindranath’s trip to England and America in 1912–13 was his third visit to the West, and the impressions were recorded in a collection of small pieces in a text which was given the name, Pother Shonchoy. In one of the essays, he talks about the intellectual world in England which, as Rabindranath put it, bore no resemblance to the arrogance and pomposity demonstrated by the members of the British ruling class in India. Here, one might also recall the 1916 essay he wrote, condemning a Presidency College professor’s ill words against Indians. He critiqued that men who are better suited for disciplinary roles—such as that of drill sergeant, or a jailer—have been put in charge of educating our young minds. Rabindranath’s critique of English rule in India, particularly about how India was a source of profit for them and they kept India poor, is also worthy of engagement.

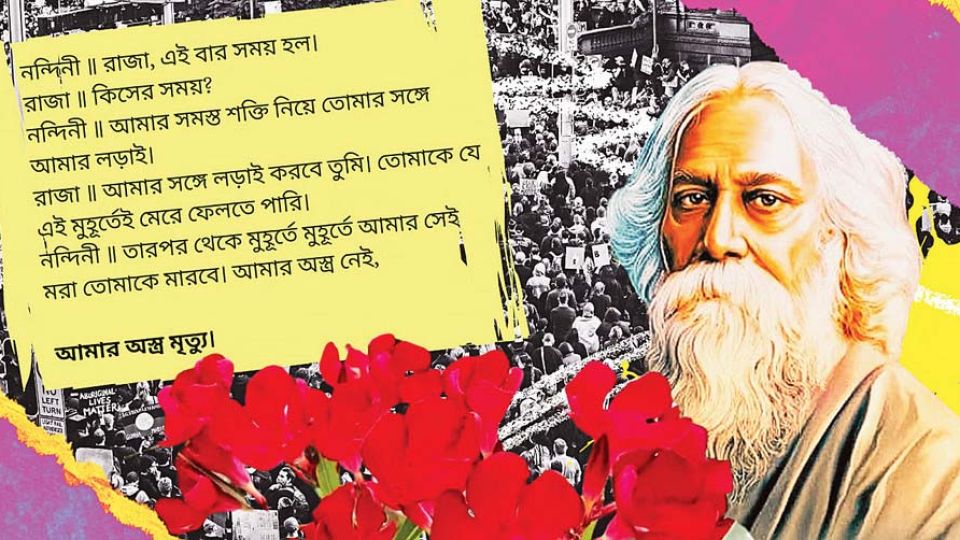

Roktokorobi (1923/1924)

Often regarded as one of Rabindranth’s staunchest protests against totalitarianism, Roktokorobi features Nandini—the woman whose only ornament is the flower roktokorobi which she wears for the man she loves—as a character who stands tall against oppressive regimes everywhere. The tyrant king’s greed is contrasted sharply by Nandini’s ability to love and her fierce determination to fight him. A play critiquing the onslaught of modernity and mindless industrialisation, Roktokorobi raises questions about what it means to be human when one is chained to a system that is intent on oppressing them.

Song lyrics

1905’s Bongo Bhongo, or the first Bengal Partition by the British Raj was rejected by Rabindranath. Songs from this era, including “Ami porer ghore kinbo na ar”, “Bidhir bidhon katbe tumi”, and “Aji Bangladesher hridoy hote”, are full of patriotic zeal and unparalleled love for Bengal. Other songs from this era include “Tor apon joney chharbey torey, ta boley bhabna kora cholbena”, “Jodi tor daak shune keu na ashe”, “Ebar tor mora Gangey baan esechhey”, and of course, “Aamar shonar Bangla”, Bangladesh’s national anthem. Lyrical, passionate, and poetic, the songs from this period continue to sway and move us—whether in music form or when appreciated for their poetic brilliance.

Gora (1910), Ghore Baire (1916), and Char Odhdhay (1934)

While out of the three novels, Ghore Baire most explicitly and expertly analyses the limits of the Swadeshi movement, together the novels reflect the thinker’s dis-ease with nationalism and how sometimes, the endeavour can be selfish. Rabindranath was an early advocate for the Swadeshi Movement, and later a critic, but his anti-nationalism is perhaps less interesting than what the novels cleverly reveal—his dis-ease with revolution itself. This is not to claim that he was anti-revolutionary, but Rabindranath’s constantly shifting, morphing ideas of both concepts—nationalism and revolution—are exhibited brilliantly in the novels, and particularly in Ghore Baire. All three novels also hypothesise the dangers of hyper masculinity and hyper sexualisation, and discuss the emergence of the new, modern woman.