July 2, 2024

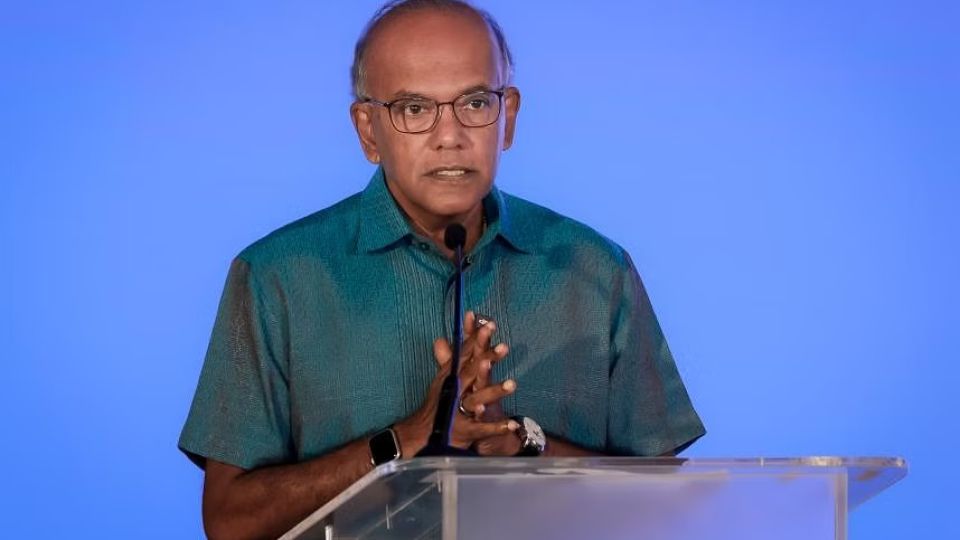

SINGAPORE – Issues of race and religion cannot be dealt with by taking a laissez-faire, race-blind approach, said Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam on July 1.

Singapore intervenes heavily to ensure social cohesion and has “a tough set of laws” to deal with the minority who choose to be nasty towards people with different characteristics, he added in a speech at a forum on non-violent ethnic hostilities jointly organised by the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Institute of Policy Studies.

Mr Shanmugam noted that in a world fraught with racial and religious tensions, the Republic – despite its status as one of the most religiously diverse places in the world – is an outlier not by chance.

The peace and harmony found here have to be attributed to its near-zero tolerance for hate and offensive speech, he said.

Mr Shanmugam spoke of other countries’ experiences managing ethnic hostilities, then detailed Singapore’s approach and laid out future challenges for the nation.

The majority of people in every society exercise restraint and treat those of other ethnicities and religions with civility, he said. But if the minority who do not are not dealt with under the law, they will eventually set the tone for an increasing number in the population.

While they might not move a majority in society, it is enough to polarise society and create enough hostility to incite violence, he added.

To stop this from happening, Singapore has, among other laws, the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act, which gives the home affairs minister the power to issue a Restraining Order against religious leaders who engage in inflammatory speech.

On top of the legal framework, the Government heavily intervenes to promote social cohesion and ensure that government policy is not organised around ethnic lines, Mr Shanmugam said.

He cited the example of Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) in public housing, saying that allowing natural market forces to take hold would see neighbourhoods with more expensive flats, such as Ang Mo Kio and Bishan, populated with 90 per cent to 95 per cent Chinese.

Introduced in 1989, the EIP sets ethnic quotas on flat ownership within each Housing Board block and neighbourhood to prevent ethnic enclaves from forming. About 75 per cent of the Singapore population are ethnic Chinese.

The Government had swum against the natural current “at some political cost”, Mr Shanmugam added, noting that many people mischaracterise the policy as being against minorities, as it means that minority ethnic groups cannot sell their flats to a larger segment of the population.

Beyond enclaves, the consequence of allowing segregation to take place along ethnic lines is schools becoming segregated over time as well, affecting integration, he said.

Mr Shanmugam also argued that the Chinese, Malay, Indian and Others (CMIO) classification on identity cards should stay, although there had been calls to do away with it.

“Isn’t it better to understand that there are differences, and then deal with those differences… Capture the data and see the progress of the different communities, try and bring everybody up and, at the same time, overlay it with a Singaporean identity. Aren’t we stronger for that?” he said.

The CMIO classification is not intended to create division, but to help the Republic build a stronger and more united society, as well as to reduce ethnic tension, he added.

Mr Shanmugam said people in Singapore may be dismissive of cautionary tales from overseas, including Myanmar’s Rohingya crisis, which brewed over escalating tensions between Buddhist and Muslim communities in Rakhine state.

But Singapore is not all that different, the minister said.

“I would not be so dismissive. Because you have to ask – why are we different?… We could have been anywhere in the continuum,” he said. “We’re different only because we understood the causes of these problems… and worked very hard to prevent those causes from arising.”

A strict approach towards hate speech

Mr Shanmugam said notwithstanding the right to free speech, the Singapore Government draws the line firmly when it comes to words or actions deemed offensive to other races or religions.

This is not always the case overseas, where the prevailing argument is that speech attacking different ethnic groups should be allowed in the name of free speech, he said.

“This ideology of free speech has prevented people from thinking honestly and sensibly about how societies, human beings actually behave,” Mr Shanmugam told the audience.

“It’s almost as if logic is suspended when you throw the term ‘free speech’, then you can stop all thinking and you just have to accept the ideology.”

In contrast, founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew never allowed logic to be suspended and understood how human beings actually behave in society, he noted.

Because of this approach, nobody has thought of expressing his or her opinion about the Quran or any other religious text by burning it here, he said. He contrasted this with what happened in Sweden in 2023, where a series of Quran burnings took place.

“In Singapore, if you try burning the Quran or the Bible, or any religious book or symbol – your next appointment, and it will be involuntary, will be with the ISD (Internal Security Department), and if you are not detained, you are more likely to be charged for this, and certainly you will see the insides of our prison,” he said.

Citing the Republic’s tough laws against the incitement of racial and religious hatred, including a strict approach towards hate speech, he said other countries might be shocked that Singapore had caned and jailed a Chinese man who had put up graffiti that read “Malay Mati” at an MRT station.

In contrast, the US Supreme Court has said that inflammatory speech, even speech advocating violence by the Ku Klux Klan, is protected unless it is directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action.

If there are no laws to prevent people in Singapore from engaging in hate speech, a small minority of people will set the tone for an increasing number in society, Mr Shanmugam reiterated.

This is a dynamic seen in Europe, he said, where what starts out as an extreme viewpoint can slowly gather momentum.

“Over time, you see how the so-called far-right parties gain tremendous strength, basically on a variety of factors, including an anti-immigration and anti-minority sentiment,” he added.

Mr Shanmugam also argued that debates will only spiral downwards if hate speech is allowed in the name of free speech, under the “great ideological belief that a lot of debate produces understanding and tolerance”.

“A lot of heat produces light. I don’t believe that when it comes to these sorts of issues. A lot of heat and a lot of debate just spirals downwards, into more and more extreme speech,” he said.

Mr Shanmugam went on to say that actors can take advantage of the situation for a variety of reasons – a common one being politics.

He said: “You appeal to people along racial lines, ethnic lines, religious lines, it’s identity politics, and you see that happening all over.

“Right now, right today, look at the headlines. Who is winning elections in Europe? Who is leading in the US? Politicians, leaders who work along ethnic lines, who work to divide communities.”

Singapore’s legal framework for dealing with such issues will continue to be strengthened, he said. Workplace discrimination, for instance, will be addressed through upcoming workplace fairness legislation to be introduced in Parliament later in 2024.

Mr Shanmugam said this is an important piece of legislation, which signals that employment discrimination along ethnic or religious lines is unacceptable.

“If employers breach that, there will be consequences,” he added.

Differing reactions to external events

While Singapore’s approach has worked well so far, Mr Shanmugam said it is being challenged on two fronts: social media, where hate speech can travel much faster, and the population’s differing reactions to conflicts outside of Singapore.

He noted that there is plenty of disinformation in the online space, including hostile information campaigns from foreign actors that can condition people to discriminate against other ethnicities.

In addition, different ethnic groups tend to react differently to conflicts outside of Singapore, and such differences can also be exploited to stoke ethnic hostility.

“This is often amplified by people subscribing to different sources of information, their own echo chambers, based on their own sympathies and affinities,” the minister added.

Mr Shanmugam cited an opinion poll conducted by the Ministry of Communications and Information on the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

The poll found a clear, sustained difference in how older, better-educated Chinese viewed the conflict, compared with other demographic groups, he noted. They were more likely to think that Russia’s aggression is justified, and were more likely to blame the West for the conflict, and think that China’s support for Russia is acceptable, he said.

The same is true with the Israel-Hamas conflict, he said. Other polls have found that “not all groups feel equally strongly” about the matter, while members of the Malay-Muslim community are especially moved by it.

Such external events “can pull our population in different directions”, and make it more challenging for the Government and society to “hold together in a united way”, he said.

So while racial and religious harmony is now a lived reality of Singaporeans, it requires constant attention and effort, Mr Shanmugam stressed.

“The Government will continue to do its part. We will continue to look at what else is needed again, and where laws need to be changed. We will change them and explain them,” he said.