September 4, 2024

SHANGRI-LA – About seven years ago, 33-year-old Tsering Dondrub, a business owner in Shangri-La county, Diqing Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Southwest China’s Yunnan province, purchased three traditional Tibetan houses in Wugong village, Xiaozhongdian town of the county, a half-hour drive from downtown area.

The three freestanding houses built nearly half a century ago had been unused for five years and would maintain this status for another three years until a bookstore brand moved in for its new branch.

Shangri-La was a key staging post in the Yunnan-Xizang branch of the Ancient Tea-Horse Caravan Route, a trade route that started in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and prospered in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911) connecting Pu’er in Yunnan with Lhasa in today’s Xizang autonomous region.

It continues to be an important point along the north-south National Highway 214, which starts from Qinghai province, runs through Xizang and Yunnan’s Shangri-La, Lijiang and Dali, and ends in Pu’er. There are 26 ethnic groups in Shangri-La and about 33 percent of the population are of the Tibetan ethnic group.

Wugong sits just beside the highway. Villagers used to live by growing highland barley and raising yaks and sheep. About 20 years ago, there were 67 people and 10 households, which has expanded to 139 people and 31 households.

Born into a family of blacksmiths, Tsering Dondrub and his father kept refining their skills in making machetes and tableware in their spare time.

With the national highway, a high-speed railway and an airport, Shangri-La, the mysterious region described in the novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton published in 1933, has become easier to access in recent years.

Tourism has boomed, bringing visitors from home and abroad to the outlying village, who have showed a strong interest in traditional Tibetan culture.

Having been often invited to craft Tibetan knives and containers by tourists, Tsering Dondrub and his father opened a workshop beside the highway, which soon became lucrative.

Since 2009, under the trademark Kasa Dao (Kasa Knife), Tsering Dondrub has been running the business of making and selling traditional Tibetan products both online and in shops. By 2021, with integrated businesses, including rural tourism, iron products and ethnic cultural products, he has seen revenues exceed 7 million yuan ($985,125).

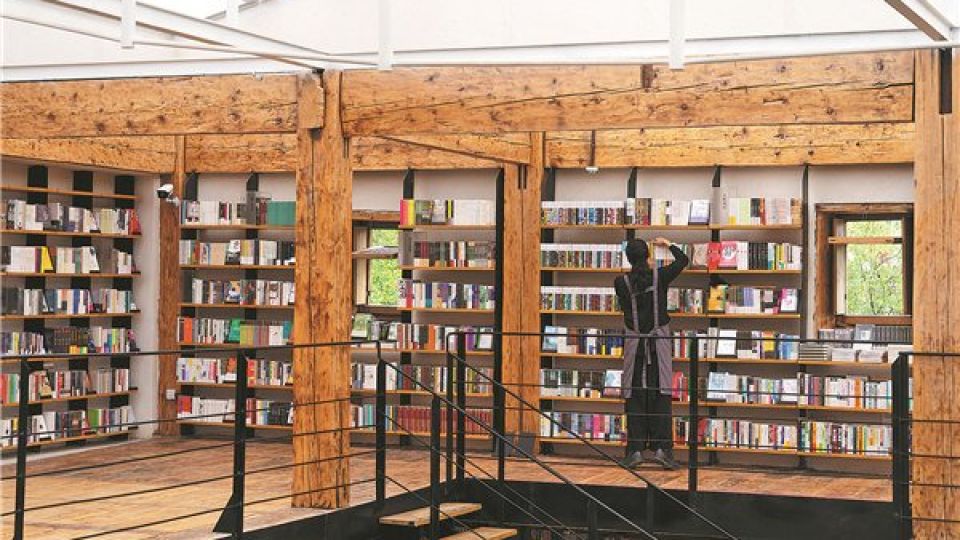

Guests and tourists at the bookstore on its opening day in late June. PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY

He bought the three old houses seven years ago, not far from a reservoir, with plans to renovate them into hostels. However, by 2020, Tsering Dondrub had still not found a partner who was willing to renovate the three houses, which otherwise would be torn down.

In May 2020, Chinese bookstore brand Librairie Avant-Garde, headquartered in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, opened its new branch in a village in Shaxi ancient town of Dali Bai autonomous prefecture, Yunnan. Its founder Qian Xiaohua and rotating chairman Zhang Ruifeng soon started looking for other opportunities in the province.

They came to Shangri-La at the invitation of the local government because, since 2014, their bookstores renovated from derelict old houses in rural areas have successfully brought vitality back to those hollowed-out villages, setting good examples for rural vitalization in China.

They were taken to the commercial areas in Dukezong ancient town and other places, but Qian always prefers a venue with a good view that has not yet been touched by commerce.

“We always want to create a place to realize our idealism about bookstores, rather than simply for business,” Zhang says.

When Tsering Dondrub first showed them the three ramshackle Tibetan houses, they were quite impressed, but there were dozens of such houses nearby. A year later, when they viewed the houses again, Qian decided to rent them. Otherwise, they were very likely to be torn down like other deserted houses.

They invited architect Zhao Yang to design the renovation plan.

Zhao, a graduate of Tsinghua University and Harvard University, is now based in Dali. For years, he has been trying to put his architectural idealism into practice — to talk to nature with an open mind.

“A good house is like a tree. If a tree grows well, it’s because it grows in the right place — it can adapt to the local water, soil and sunlight conditions,” he was quoted in a previous interview. “What I have learned from building houses in rural areas is that there are no definite rules about design, which changes according to local conditions.”

Before the bookstore, Zhao already completed two works in the places lived in by Tibetans. One is the Nyangchu River tourist center, which was completed in 2009 and is located in Nyingchi county in Xizang along National Highway 318.

Another is the Sunyata Hotel in Yunnan’s Dechen county, which opened at the end of 2018 and sits across the holy Tibetan Meili Snow Mountain. Its predecessor was the renowned Migratory Bird Inn.

In 2022, when Zhao first saw the three rundown Tibetan houses standing in the field, he says he felt this place fits the bookstore’s brand ethos.

Typical of traditional Tibetan houses in Shangri-La, the three houses represented the architectural system established by people who had lived there for hundreds of years.

“Their architectural form, the slope of the roof, the way it handles rainfall, and the choice of materials all blend harmoniously with the surrounding environment,” Zhao says. “So, we need first to understand and appreciate them before considering whether we can add something new.”

Zhao and his team carefully entered the houses, closely observed them and found people like Tsering Dondrub to tell stories about the village.

Zhao was surprised to find that the wooden structure of the three houses is different from those of the houses of the Han people in their building logic.

In the wooden structure of a Han house, the pillars on the first and second floors are often a single piece of wood. However, the pillars on the first floor of a Tibetan house were shorter, more slender and simpler than those on the second floor. The first floor was inhabited by livestock and the second floor by people.

“That is fascinating for an architect like me, who grew up with a modern architectural education. I see it as a precious anthropological legacy that we should carefully preserve,” he says.

What also fascinates Zhao is the textured surface of the pillars on the first floor that reveals how they were made — possibly with just an axe — and a painting featuring the eight auspicious symbols every Tibetan household has, along with other anthropological information, which he managed to keep.

With an altitude of more than 3,400 meters, Shangri-La sees its temperature drop to about — 20 C in winter and people would open small windows on the thick rammed-earth walls for insulation and security, making the rooms so dark that during the days, people needed artificial lighting indoors.

In summer, Shangri-La enjoys abundant sunshine, but rich rainfall causes problems for people living under roofs made of wooden tiles, which they regularly need to replace.

Zhao found that the wooden structures were well-preserved, but the roofs had fallen into disrepair.

Considering that a modern bookstore needs proper lighting, Zhao supplanted them with roofs made of translucent polycarbonate panels and galvanized steel roof trusses, inspired by the sunrooms widely used in Shangri-La.

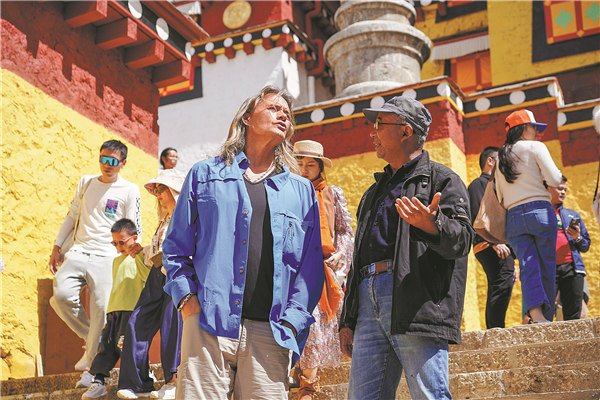

Residents from the nearby villages attend the opening ceremony of the bookstore. PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY

The three houses were renovated for different purposes — books, coffee and creative cultural products.

“We tried our best to preserve all the wooden structures in the original space,” Zhao says.

“We made the smallest changes to the inner structure, so the second floor of the cafe is like a museum of the traditional residences in Shangri-La. We lifted the roof to let light in and brighten the residence.”

Another fascinating point is that each house had a granary. Builders left a square opening on the rammed-earth facade and covered it with wooden slats for ventilation.

“Since we don’t need granaries in a bookstore, we removed them. We transformed the openings into doors and built concrete walkways that connect the three houses and with the land, which is an important part of my design,” Zhao says.

Zhao believes that the bookstore should be an outgrowth of the vast land on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, helping people connect with the soil and experience its authenticity. He created the walkways to encourage people to go out and stroll through the fields, mountains, rivers and clouds.

The building process was by no means easy.

The construction team coming from outside knew that they needed to delegate part of the work to the villagers according to local customs. After the harvest in September, villagers were free so the team hired them to tear down broken walls to increase their incomes while building good relations with them.

However, the villagers lacked the required skills, so the construction team had to carefully instruct them.

Another problem was rebuilding the rammed-earth walls to enclose the yards. Having no idea what to do, the team members turned to the villagers. To their surprise, though this type of wall had almost been abandoned in Shangri-La, elderly villagers still retained memories of building houses with their fathers.

“I was so frustrated that I thought we should abandon the plan of building rammed-earth walls. However, with the help of the local people, we continued. Nothing is more ‘site-specified’ than this. Looking back, it is such a gift from the land to our project,” writes the on-site architect Liao Fuhong in his construction notes.

Offering a view of the Haba Snow Mountain across the Jinsha River, the upper stream of the Yangtze River, the bookstore houses 15,000 books on humanities and social sciences and 100 types of creative cultural products with local elements. Readers can also find books about local cultures, geography, languages and history.

“It’s great that there are so many books about Tibetans and Shangri-La at the bookstore. These books can connect different cultures,” Tsering Dondrub says.

In the house for creative cultural products, people can find refrigerator magnets inspired by natural and cultural landmarks, such as the Ganden Sumtseling Monastery, an important Tibetan Buddhism site in Yunnan, the Haba Snow Mountain, prayer wheels, bookmarks inspired by Tibetan scripts and brooches inspired by Tibetan Opera masks.

At the cafe, visitors can have a highland barley-flavored latte or yak butter latte.

“The bookstore showcases how distinctive the old houses in Shangri-La are innovatively revitalized and imbued with new content and new appearances with more possibilities for the future,” Zhang says.

The Shangri-La branch is the sixth rural bookstore of Librairie Avant-Garde since its first one in Bishan, Anhui province, in 2014.

“We have rural bookstores in the Bai, She and Yi ethnic areas — and now the Tibetan ethnic area,” he says.

In Lost Horizon, Hilton describes a library in Shangri-La that has a large collection of books, ancient and modern, domestic and foreign.

“Zhongdian was renamed Shangri-La (based on the introductions in Hilton’s work) in 2001, so it must have an idealistic bookstore,” Zhang says.

However, building a bookstore in such a remote place is not only symbolic. In the short term, the bookstore, like its many precursors, can boost tourism, the economy and culture.

“Every place has its unique history. What we can do is feature the local forte through our platform so that tourists can see traditional local architecture or learn about the local culture, history and geography through the books we present,” Zhang says.

Since its opening, the revenue reached 270,000 yuan in the first month, which “is better than expected”, Zhang says, adding that “maybe it’s because summer is the peak season for Shangri-La tourism”.

In other seasons, especially winter, “business might be sluggish because the altitude naturally prevents many people from visiting, but we will keep going”, he says.

In the long run, the bookstore will exert a seminal influence on the residents with books and various cultural events, he says.

“We cannot turn people into book lovers within six months. But over five years, or one or two decades, the residents will see so many people reading and caring about their history and culture, which will not only help increase their incomes but also encourage them to cherish, protect and pass on their culture and be proud of it,” Zhang says.

In September, Librairie Avant-Garde will open a Lisu ethnic bookstore in the Grand Canyon of the Nujiang River, on the Gaoligong Mountain bordering Myanmar, duplicating its previous experiences.

Chinese poet Yu Jian, 70, a guest attending the bookstore’s opening ceremony, said that he was surprised to see a bookstore in such a “remote” place.

“The bookstore is great but I am wondering how they will survive because there aren’t many readers of Mandarin books since most Tibetan people don’t understand Mandarin,” Yu says.

“However, the bookstore transcends traditional models. It’s not about making money. It’s more like a ‘temple’ inspiring people’s respect for books and bookstores.”