September 30, 2022

JAKARTA – It takes a village to raise a child, but what happens to their development when the village is in lockdown? Parents and experts look at what worked and what kinds of problems emerged during the pandemic.

At the height of the pandemic, parents had to scramble at getting their children to focus on a computer screen. Helping their children, especially very young children, learn online was not easy for parents, many of who were also juggling other day-to-day responsibilities.

This was the case for Muhammad Faried Kasaugie, a father of four who was still at university in 2019, the year before the pandemic struck, who relied on his wife to help the kids with online schooling.

“The atmosphere at home was inconducive [to learning] and a bit chaotic, especially for my wife, because she needed to prepare the children for their classes online and prepare household needs as well,” said the native of Tangerang, Banten.

“When the pandemic was at its peak, the children had their classes at home and played indoors. They did most of their activities inside the house.

“Since they didn’t meet their teachers physically, I think their [learning and] socialization were not as effective. They may know the learning materials, but children still need to meet each other offline for their physical and mental growth,” he said.

Latifah Fitriani Rakhman, a 29-year-old from Malang, had a daughter who was just 2 years old when the pandemic arrived in Indonesia, and the family of three had to drastically reduce their outdoor activities.

“We lived in Jakarta back then, and usually we would go out of the apartment every afternoon to play in the park, but when the pandemic came, we did not leave the unit at all, except for urgent matters,” she recalled. “Typically, we would attend an outdoor playgroup once a month, but we had to move it online.”

Fortunately for Latifah, the online playgroup was effective for her daughter. “The [playgroup] activities were mostly playing and singing. They had fun meeting their friends and instructors and seeing other people’s expressions, but not for [a long period of time].”

The online playgroup activities went well for Latifah’s daughter, but this was an exception rather than the rule. Many parents noticed an increase in speech delay, gadget addiction and learning loss in their children during the pandemic.

Mutiara Astari is one of them. She recalls being baffled on reading about a 5-year-old with nutrition problems who also had delayed speech development that impeded the child from communicating their food preference.

“There are many cases of children with speech delay around me. It seems to be common these days to see children with the issue,” said the 31-year-old housewife from Malang. “It makes me wary [about my own].”

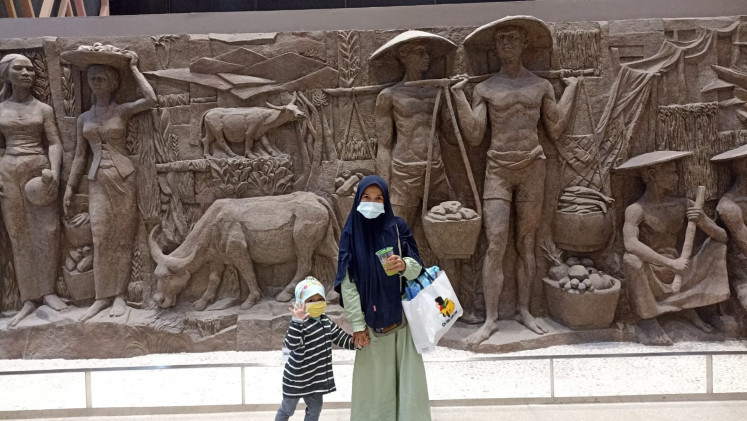

Adaptable learner: Latifah Fitriani Rakhman feels fortunate that her daughter, who was just 2 years old when the pandemic started, was able to adapt relatively well to her outdoor playgroup moving online. (Courtesy of Latifah Fitriani Rakhman) (Courtesy of Latifah Fitriani Rakhman/Courtesy of Latifah Fitriani Rakhman)

Silent battles at home

Faried’s four children are now 6, 5, 4 and 1. They play with toys, draw pictures and read books together when they are confined indoors.

“I have many children so they can play together,” said Faried. “We don’t give them [access to gadgets] often, including the television. We limit [TV time] to Saturdays and Sundays only.”

Latifah, on the other hand, had a different challenge with her singleton, so she armed herself with more tools to help keep her daughter entertained: “We had to purchase more toys than before [the pandemic] so the little one wouldn’t get bored at home.”

She is not alone. Ramadhan Niendraputra, head of category development at e-commerce company Tokopedia, revealed that transactions in the mother and child category was still growing now, long after the pandemic’s peak.

“This growth is not only driven by big cities,” said Ramadhan, noting that many customers were located in smaller cities like Parepare in South Sulawesi and Jepara in Central Java. “We [believe] Indonesian parents are more educated about buying their parenting needs online.”

Thanks to the internet, parents can also scour thousands of sites for parenting tips and tricks. As for Mutiara, she has joined several online support groups where parents can exchange information as well as rant.

Mutiara noticed that any speech delay in her children “usually happens due to unsupervised screen time”.

“My parenting style is not without screen time. I allow my children to use gadgets, but provide supervision and stimulation,” she said.

Jakarta-based pediatrician Citra Amelinda said that providing stimulation was akin to providing nutrition for a child’s physical development. Reports abounded during the pandemic that many children were experiencing speech delay and social detachment, and she stressed that in such cases, parents needed to be alert and agile in watching for early warning signs.

“For example, if the child is one year old and they still make no effort to communicate, this is a warning sign. You don’t have to wait until they are two years old. The earlier they are diagnosed with speech delay, the sooner it can be dealt with,” said Citra.

“As for social detachment, parents must spare time to have quality interactions with their children. If you [live] far apart, use video calls, that’s OK.”

Mimicking behavior: Agung Pranggono (seated, second left) from Grahita Indonesia, an applied psychology institute in Bandar Lampung, Lampung, emphasizes that children take social and other developmental cues from their environment, including the objects and the people around them. (Courtesy of Grahita Indonesia) (Courtesy of Grahita Indonesia/Courtesy of Grahita Indonesia)

Inherited problems

Contrary to the growing belief that addiction to gadgets is affecting cognitive development in young children, psychologist Agung Pranggono from Grahita Indonesia, an applied psychology institute in Bandar Lampung, the provincial capital of Lampung, is not keen on blaming gadgets for all developmental delays in children.

“There are so many factors when we talk about developmental delays, and we cannot simply point our finger at whatever convenient scapegoat we can find for these problems. There are cases in which children are attached to gadgets, but they still develop normally,” Agung said.

Priska Parsaulian, the creative director and cofounder of Montessori Madness in Bekasi, West Java, which provides enrichment classes for children aged 6 months to 6 years, has a similar view.

“Gadgets can offer benefits, especially for language and cognitive development in children. However, they are not recommended for stimulating motor development in children,” Priska said.

“From our observations, children aged 18 months to three years need actual motor skill activities in using their fingers. This is important as preparation for writing [skills]. Today, children cannot hold pencils properly because of the lack of fine motor stimulation,” she added.

Agung also elaborated that from his observations, some parents might unconsciously impede their children’s development due to unresolved psychological issues, and the pandemic might have brought a latent problem to light instead of directly causing one.

“Fetuses can feel stressed too. If the mother is stressed during pregnancy, the child will be born in a stressed mental state,” he explained. “There are also parents who think they have already given proper stimulation to their children, but they’re not building a conversation. It’s one-way [communication] in which the child doesn’t even feel the need to respond.”

A problem usually develops between children and gadgets when communication is only one-way. Experts like Citra and Agung therefore believe that digital devices are safe for children to use, as long as they still experience two-way social interaction.

“We need to remember that gadgets are [inanimate objects]. Children learn from living [things],” Agung said.

“Children are like photocopy machines. Their whole lives, they copy the things around them. Even when their access to the outside world is limited, they still have their parents.”