September 23, 2024

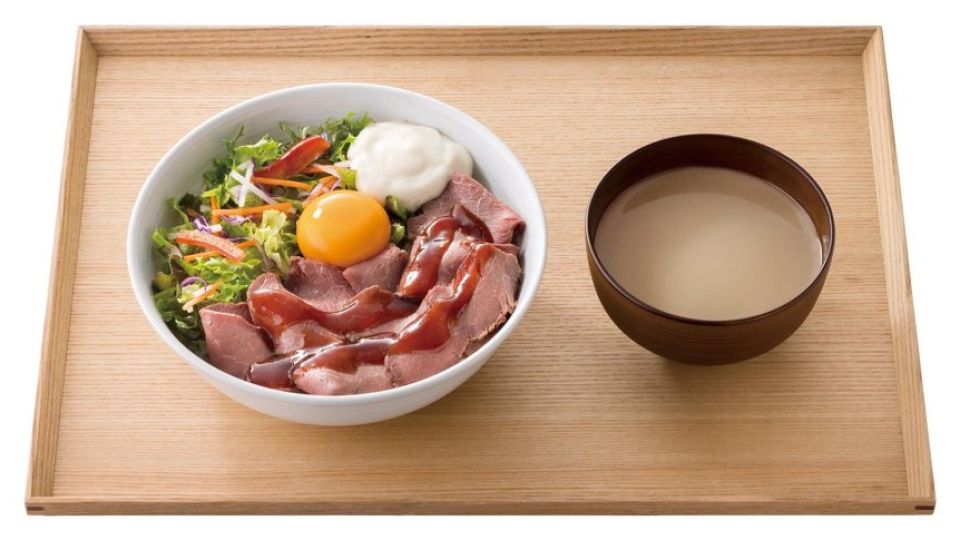

TOKYO – Yoshinoya, the famous gyudon (beef bowl) chain, served up ostrich rice bowls as a limited-time menu option in late August, looking to the flightless bird as a means to stabilise volatile beef supplies.

For a country renowned worldwide for its exquisite washoku or traditional cuisine and premium high-quality produce, Japan suffers from dire food security challenges at home.

It is a net importer of food, particularly for day-to-day consumption, making it susceptible to external shocks to shipping lines and the volatility of inflation. Even the food it produces domestically is vulnerable to challenges like climate change and an ageing workforce in the agricultural trade, with few successors.

Yoshinoya president Yasutaka Kawamura told a news conference in August that the vagaries of supply chains for beef, which it imports from the United States and Canada, led the company to buy an ostrich farm in Ibaraki prefecture.

“Yoshinoya’s operations have always been affected by the situation surrounding beef,” Mr Kawamura said. “To grow our business while protecting beef bowl operations, we need to diversify to reduce risk.”

While Yoshinoya also has pork and chicken options on its menu, the ostrich venture through its subsidiary Speedia marks a major shift for the 125-year-old company. Now, Yoshinoya is also selling skincare products made using ostrich oil as a means to raise funds to secure more ostrich meat in the future.

The ostrich bowl menu has been discontinued for the time being, after all 60,000 bowls made available were snapped up despite costing 1,683 yen (S$15) each – about three times the price of a beef bowl.

The venture comes as beef prices soar. Japanese wholesale prices of frozen US beef belly used in gyudon were up 80 per cent on the year at 1,450 yen to 1,530 yen per kilogram, and Yoshinoya raised gyudon prices in July for the fourth consecutive year.

Meanwhile, supermarket shelves across Japan were also emptied of rice for weeks this summer, forcing retailers to set a purchase limit of one 5kg bag per family per day.

In May, an orange crisis stemming from shortages in Brazil – a major supplier that was reportedly affected by extreme weather and fruit tree disease – resulted in beverage manufacturers pausing production of their orange juice products.

Japan imports about 90 per cent of the oranges used for juices.

This followed a paucity of potatoes from 2021 to 2022 that led fast-food chains, which import potatoes, to restrict sales of French fries.

Japanese potato chip manufacturer Calbee, which sources 90 per cent of its potatoes domestically, was also hit by a bad crop.

But the ongoing rice shortage in Japan, where more than 500 different varieties are grown, has hit hardest at home, given that it is a staple in the diets of most Japanese people.

Private-sector inventories were at their lowest level in June since comparable records began in 1999. And after accounting for supply to commercial eateries, there was not enough to go around supermarkets and grocers, which found their shelves soon wiped clean of rice.

The staple is now slowly returning as autumn harvests begin – albeit at a noticeable premium. Prices have soared by as much as 50 per cent, and it is now not uncommon to find 5kg bags of domestically grown rice that cost above 3,000 yen.

Ninety-eight per cent of the rice consumed in Japan is home-grown, with the remainder imported and used almost entirely in foreign cuisine restaurants. Japan’s short-grain rice is used in everything from onigiri rice balls to bento meal boxes and sushi, and substituting it with longer-grain overseas rice is a non-starter.

This has been unnerving for many Japanese. A 31-year-old father of one, who wanted to be known only by his surname Nagase, told The Straits Times: “Rice is indispensable in our home, and the prospect of a future where even this is uncertain bothers me.”

The shortage has been blamed on a confluence of factors, primarily lower yields in 2023 due to intense summer temperatures that hurt the quality and quantity of the crop. Some farmers have begun cultivating heat-resistant varieties, although this accounts for only about 15 per cent of the total rice planted.

The first-ever Nankai Trough mega-quake alert in August is said to have also triggered a bout of panic buying as people sought to increase their disaster preparedness.

An influx of tourists has also been cited as one reason for the shortage, although they at best would contribute to an increase of 31,000 tonnes, or just 0.4 per cent of overall demand.

Agriculture Minister Tetsushi Sakamoto told reporters on Sept 6 that he expected rice prices to ease. He said: “We will monitor shipments and inventories to ensure that rice reaches supermarkets and other retailers smoothly, and urge consumers to respond calmly.”

The Mainichi newspaper, in an editorial on Sept 12, described the rice shortage as “a failure of government policy past and present”.

“Japan may be losing the capacity to respond to unexpected demand fluctuations. The supply base for the staple food needs to be inspected,” it said. “There is concern that while rice to fulfil commercial demand was secured, retail supplies became depleted.”

The current shortage has revealed the fragility of the rice supply mechanism, which began in the 1990s as a means to protect the crop from price fluctuations, to avoid flooding the market with more supply than demand.

The Sankei newspaper said in an editorial on Sept 18: “Rice is the foundation of Japan’s culture and food security, and a long-term strategy to ensure stable supply should be the government’s new top priority.”

The Canon Institute for Global Studies (CIGS) think-tank’s research director Kazuhito Yamashita, a former bureaucrat with the Agriculture Ministry, urged the government to relax its agricultural policies to control annual rice production volumes.

Underscoring the country’s reliance on imports, Japan’s calorie-based food self-sufficiency rate, defined as the percentage of consumed calories produced domestically against what is needed to meet the nutritional intake, stood at a paltry 38 per cent in March 2024. This is far short of its target of 45 per cent by March 2031.

Driving home how Japan has substantial food security risks, Dr Yamashita said in a paper on the CIGS website: “If imports were disrupted – a serious crisis where neither wheat nor beef can be imported – livestock farming, which relies on imported grain, will be almost decimated.

“If food imports are cut off, raw materials like oil and fertiliser cannot be imported either.”