October 26, 2023

KOLKATA – The route to Totopara, a village located close to the Indo-Bhutan border in India’s West Bengal state, is scenic, as travellers drive past verdant tea estates and lush forests in the Himalayan foothills.

But it is also a difficult one with unpaved stretches on dry riverbeds that are inundated during the monsoon, cutting off Totopara entirely.

It is in this remote village, more than 700km away from state capital Kolkata, that a community-led initiative has sprung up in recent years to protect Toto, a Tibeto-Burman language classified as “endangered” by Unesco.

Spoken by around 1,600 members of the Toto tribal community, the language has been throttled by an education system and an economy that oblige its speakers to learn and transact in major languages in the region – such as Bengali, Nepali and Hindi – instead of their mother tongue.

But Toto has found renewed vigour as its speakers strive to retain their identity and way of life, while pushing back against the economic and cultural onslaught of the dominant languages.

A script for the language, along with 33 letters, was developed in 2019, giving the community a sense of pride and avoiding the use of scripts of other languages such as Bengali that fail to capture unique sounds of the Toto language.

Young volunteers are now popularising its use by teaching the script to local children, besides documenting traditional Toto songs and writing new ones in the language.

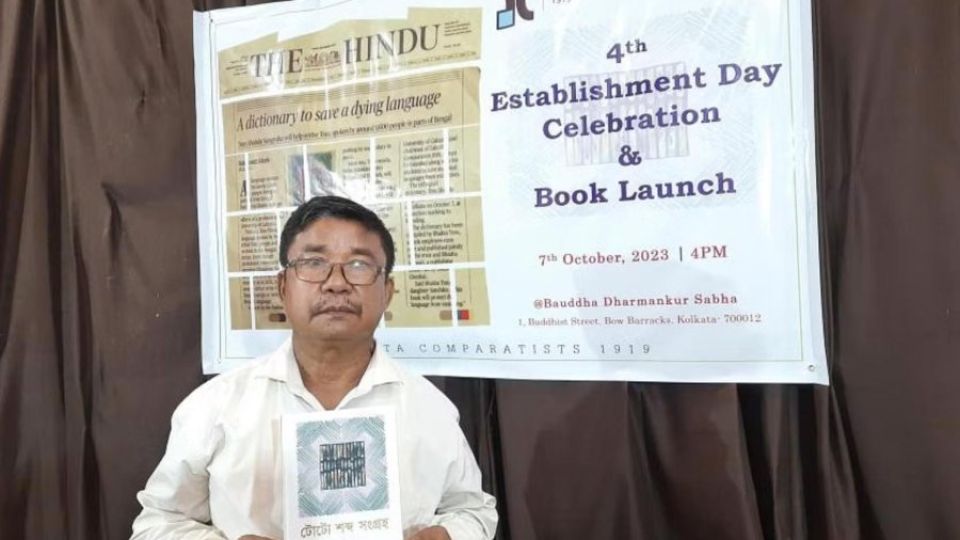

The language’s first dictionary, a compilation of around 1,200 Toto words and phrases along with their English and Bengali equivalents, was also released in Kolkata on Oct 7.

“The moment we step out of our house, we are forced to speak Bengali, Hindi or Nepali,” rued Mr Bhakta Toto, 60, a bank officer from Totopara, who compiled the dictionary on his own over many years.

“A lot of words from other languages have therefore crept into our language, which is why it is important to document Toto words so that the next generation can read and write them,” he said.

For instance, kaibu, the Toto word for a step, is gradually being replaced with the Bengali equivalent, shiri. Dui, which means verandah, has also given way to baranda from Bengali.

Used as bonded workers by the Bhutias, a dominant tribal group in the region until around the mid-19th century, the Totos today primarily live off their land, cultivating crops such as betel nut, and rearing livestock.

Daily wage work at farms and construction sites is another key source of earnings for this community that counts just around 10 graduates and is almost entirely based in Totopara.

The Totos’ existence on the margins mirrors the linguistic plight of many other remotely located communities in the country. But just as the Totos, who are fighting back, several threatened linguistic groups are endeavouring to protect their languages.

In central India, Gondi speakers have sought to standardise their language spoken by around 2.9 million Gonds and generate a shareable lingua franca through public workshops.

Farther up north, in Uttarakhand state, volunteers have organised pop-up language classes and trained adult teachers to help preserve Raji, a language spoken by fewer than a thousand members of traditionally nomadic communities.

In Bihar in the east, activists have developed tools to give Angika, a vulnerable language, greater space online.

Any language is integral to a community’s identity and offers insights into its world view. For example, the family of Great Andamanic languages, spoken in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal, have a word (raupuch) to describe a person who has lost his siblings, implying how important family kinship is for them.

India is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world, with the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (PLSI), a civil society initiative launched in 2010, documenting as many as 780 languages.

The state, however, has been less magnanimous in recognising this diversity. Its decennial census, which records only languages with more than 10,000 speakers, listed 121 languages in its 2011 edition, wiping the others off the map.

The country’s linguistic diversity is further pared down with the federal government recognising only 22 of these languages as official, which it is constitutionally obligated to protect and nurture.

The vast majority of the “unofficial” languages – victims of official apathy – are spoken by marginalised communities, primarily around the Himalayas and in less developed regions of central India such as Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha.

The Unesco’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger estimates around 170 languages are under threat in India, more than half of which are Tibeto-Burman languages in the north-east.

These languages are endangered, it said, because learning them has become “unfashionable”. They are no longer transmitted from one generation to another and have limited state support, which also results in their absence from school curricula.

In Totopara, demands for Toto language education in schools, including government ones, have fallen on deaf ears. But that has not stopped Mr Soney Toto, 28, and some of his friends from teaching the language and its script to children at a private school in the village.

Once every week, around 95 children from the Chittaranjan Toto Memorial Education Centre – both Totos and non-Totos – gather to learn the language and master its nasal consonants such as “ng”.

“While we assimilate with the world outside, we are also striving to keep our identity alive,” said Mr Soney Toto (all Totos carry the same surname), who also teaches English. “We may be poor, but we are culturally rich,” he told The Straits Times.

The Toto dictionary’s publication was supported by Calcutta Comparatists 1919, a collective of humanities and social sciences scholars that seeks to bring marginalised languages and communities into the limelight.

Dr Mrinmoy Pramanick, an assistant professor at the University of Calcutta’s Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature, said the collective resists India’s “mainstream academic culture” that takes away from many the right of education in their mother tongues.

“If children are not educated in their mother tongues, they are burdened by the need to acquire another language for their education, which makes it difficult for them and causes them to lose their basic confidence and expression,” he added.

While the government has a national scheme to document endangered languages, the overall lack of state recognition and support for languages on the margins has hastened the migration of their speakers to dominant speech forms as they look out for economic opportunities.

Because of such a process, many minor languages are today used for fewer daily functions, becoming unviable for their communities and dying a silent and protracted death.

“This form of language loss is a cancer, not a gunshot,” according to Mr Frederico Andrade, co-founder of Wikitongues, a crowdsourced project that aims to archive every language in the world.

According to Mr Ganesh Devy, who led the PLSI, India may have lost around 220 languages in 50 years since 1961. This list now includes Sare, one of the world’s oldest surviving languages, which went extinct in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands when its last speaker, Mrs Licho, died in April 2020.

In Totopara, the Totos learn Bengali, which is the official and most widely spoken language in the state of West Bengal. Not just that, they also have to pick up Nepali and Hindi, which are spoken by more numerous communities in the region and with whom the Totos must conduct business.

Mr Dhaniram Toto, who developed the alphabet and script for Toto language, had to deal with this dilemma when a youth once asked him why he should learn Toto instead of English and if he could get a job by doing so.

“I told him even learning English doesn’t guarantee you a job these days,” joked the 60-year-old, a published Bengali novelist who in March was awarded the Padma Shri, one of India’s top civilian honours, for his efforts to preserve the Toto language and culture.

But Mr Dhaniram Toto also told the youth that irrespective of whether learning Toto helps him land a job or not, he has to save his language. “As a Toto, you can learn English, French, Russian or any other language, I have no problem. But you need to protect your community’s linguistic symbol too,” he added.

It is such determination that led him to create the alphabet and script for Toto in 2019, so that the language could be better documented for posterity. “Even if it is of an embarrassing standard, I told myself my language had to have an alphabet too,” he said.

“I am a pothodarkshak,” added Mr Dhaniram Toto, using the Bengali word for someone who shows the path ahead. “Maybe in another 50 years you will see that better Toto alphabets will emerge from it and the coming generations will improve it further.”