September 17, 2024

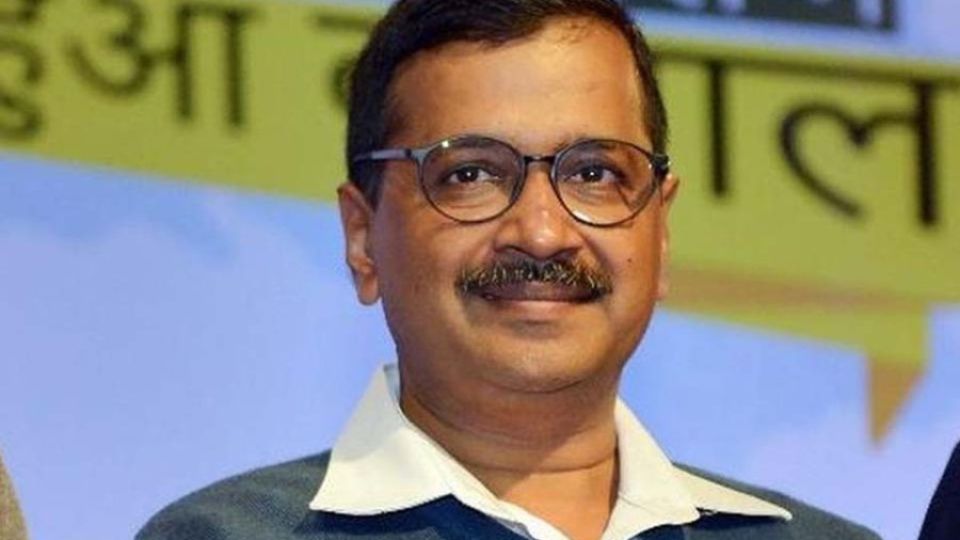

DHAKA – Barely 48 hours after Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) chief and Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal walked out of high-security Tihar jail on September 14, following bail granted by the Supreme Court in a case of alleged graft, he made the dramatic announcement of stepping down from office in a couple of days. He made the announcement while addressing a meeting of AAP workers in New Delhi. Kejriwal, who was released from prison nearly six months after his arrest in the excise policy corruption case, said, “I will only sit in the chief minister’s chair after people give me a certificate of honesty. I want to undergo ‘agnipariksha’ (trial by fire) after coming out of jail. I will become chief minister, (Manish) Sisodia deputy CM only when people say we are honest.” He also stated that, since fresh elections for the 70-member Delhi assembly are due in February, he demanded that the elections in the national capital be held in November, along with that of Maharashtra.

Kejriwal’s reasoning for his resignation has raised at least two questions. Does he believe that only a fresh electoral victory can establish his honesty? What then happens to the court’s role, which either convicts or absolves a person of charges? Can an electoral victory override a court’s ruling on a person’s culpability? There have been many instances of individuals holding constitutional posts resigning after court convictions. Kejriwal argues that, since the trial in his cases is time-consuming, he prefers to seek a fresh electoral mandate. If he leads his party to victory in the Delhi Legislative Assembly elections and becomes chief minister again, what happens if the trial court convicts him? Can electoral mandate be a substitute for judicial pronouncement?

Why did Kejriwal talk about his resignation with just a few months left for the completion of his government’s tenure? Is it a form of moral grandstanding? It is time to look at the road ahead for the maverick AAP leader both as the head of the city-state government and as a politician.

The Supreme Court has imposed a number of conditions on Kejriwal as chief minister upon granting him bail. Among these conditions, he is not allowed to visit the chief minister’s office in the Delhi Secretariat or sign official files unless necessary to obtain clearance from Delhi’s Lt Governor, who represents the BJP-led federal Indian government under the current power structure. Delhi operates largely as a quasi-state without the powers of full-fledged Indian states.

Given these conditions, there is speculation about how effective Kejriwal will be in leading his government. Key policy decisions, including the populist scheme of providing Rs 1,000 monthly to women, are pending. Then there are the issues of dearness allowance for daily wage wagers and Delhi’s logistics plan and a 10-year economic and industrial development policy. The populist schemes are important for Kejriwal and AAP in Delhi which was the base for Kejriwal’s emergence as a rising political star in 2012. But he may have realised that implementing these schemes could lead to frequent conflicts with the Lt Governor, as witnessed over the past 10 years.

Another daunting challenge for Kejriwal is leading his party in the upcoming Haryana assembly polls, where AAP is contesting 89 of the 90 seats without an alliance with Congress. Although AAP sought to form an alliance with Congress for the Haryana elections, the latter’s state unit, particularly senior leader Bhupinder Singh Hooda, opposed any tie-up. Both Congress and AAP had previously formed an alliance for the seven Lok Sabha seats in Delhi earlier this year, despite strong resistance from Congress members. The result was disastrous for both parties, as the BJP won all seven seats.

In Punjab, where AAP is in power, the party did not form an alliance with Congress for the national elections but lost most of the 13 Lok Sabha seats to Rahul Gandhi’s party. Interestingly, AAP has yet to win any parliamentary seat in Delhi, despite winning successive assembly polls since 2013 with overwhelming majorities, demonstrating that Indians often vote differently in national and state elections. AAP’s performance in the national elections in Delhi and Punjab was also impacted by Kejriwal’s vigorous campaigning, taking advantage of a 21-day freedom provided by the Supreme Court to leave jail.

Congress hopes to return to power in Haryana, where the BJP is struggling with anti-incumbency and serious internal bickering. Kejriwal faces a significant challenge in steering AAP through a two-front battle in Haryana against both BJP and Congress. Will Kejriwal manage to position AAP as a major player in Haryana’s elections after the failed alliance talks with Congress? The absence of a Congress-AAP alliance in Haryana is expected to split anti-BJP votes. The question is: to what extent will AAP impact anti-BJP votes that would have gone to Congress?

Has the corruption case against him and many of his senior party colleagues damaged AAP’s appeal, which was built on populist actions like establishing locality-based health clinics, improving education in state-run schools, and reducing water and electricity tariffs in Delhi? Kejriwal faces the difficult task of regaining public confidence and restoring his position in the opposition INDIA alliance after AAP’s poor performance in the national elections earlier this year.