May 22, 2023

JAKARTA – After Surakarta record company Lokananta (then PN Lokananta) switched to cassette tapes and stopped operating its vinyl pressing services in 1972, Indonesia’s music industry essentially lost its only means of encouraging vinyl records in the country.

There have been times when the format was thought of as dead, but later generations of music listeners have rekindled their interest in the analog format, enchanted by its grooved, tangible charm and the ritual-like process of soaking in the whole context of an album –particularly noting vinyl records’ large artworks and lengthy liner notes.

It became a novelty as it offered an experience that some would note as the ultimate inconvenience, and the antithesis of the instant gratification that digital music releases today have to offer – most of which are distressingly myopic in their delivery with the sense that they lack imagination and depth.

Vinyl records, nevertheless, have managed to stick around, even in the domestic context, as local players turned to press plants and suppliers abroad. Yet they were always subject to significant barriers to pressing music in the format and distribution in Indonesia.

Will PHR Pressing, the new, and currently only, pressing plant in Indonesia, be a catalyst in reshaping the country’s physical release landscape?

The kindling

“It’s 2022 now, and it’s no longer a fad,” Detroit musician/producer Jack White calmly said in a video uploaded on his record label Third Man Records’ YouTube channel on March 14, 2022. The video appealed to the three significant global labels, Warner Brothers, Universal and Sony, to “finally build your pressing plants again.”

With 2022 vinyl record sales towering over other formats, particularly the compact disc, in the United States (accounting for 71 percent of physical format revenues according to a Recording Industry Association of America/RIAA report), the format has undoubtedly experienced a resurgence since the mid-to-late 2000s. Vinyl has experienced its 16th consecutive year of sales growth, with the latest sales figure for 2022 at US$1.2 billion.

White opened Third Man Pressing, the manufacturing arm of his label Third Man Records, in 2017 through personal funds. A year after, vinyl sales were still on the rise in the US for the 12th consecutive year, yet Nielsen Music’s report that vinyl had experienced 9 percent growth in sales, in contrast to the past year’s double-digit growth, led some people to declare the end of the vinyl boom.

The mid-2000s started the next resurgence, but local players, mainly from the independent spectrum, were only exposed to the rising trend in the late 2000s to early 2010s. Jakarta record label Grieve Records, run by musician Uri Putra (GHAUST, Kelelawar Malam) and Sayiba Bajumi (Kelelawar Malam), were some of those who dived into the then-unknown waters.

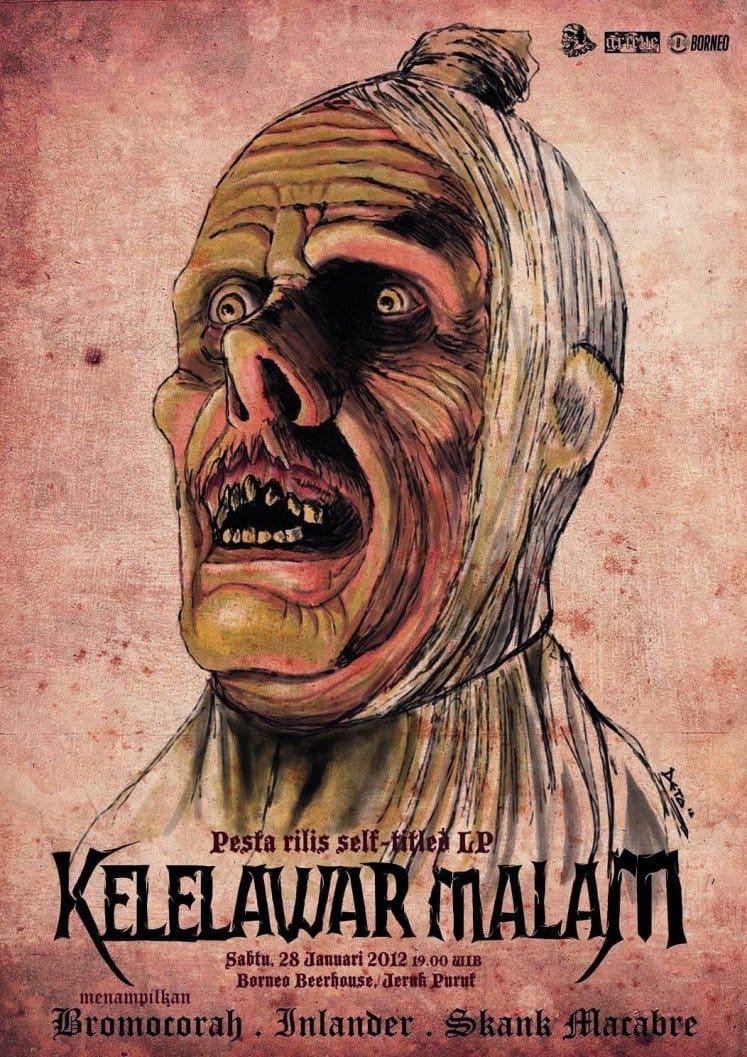

The label rereleased horror-punk outfit Kelelawar Malam’s eponymous 2010 debut studio album at the end of 2011 on random-colored 12” vinyl records pressed using recycled PVC at Gotta Groove Records, a vinyl pressing plant in Cleveland, the US.

“I think Kelelawar Malam was the first independent local release on vinyl,” Uri told The Jakarta Post on May 5. The vinyl had white, blank labels that the plant offered as a part of its do-it-yourself (DIY) package.

While some may consider the white labels as the markings of a patch-up job, it bears deeper meanings today as these white-label DIY packages and the music subcultures that relied on this packaging played a role in keeping the pressing plants alive.

Uri himself was not a stranger to the medium, in terms of the production side, as his sludge band GHAUST often released with record labels abroad on, again, formats that were close to the punk music subculture such as split albums.

In 2012, three Southeast Asian labels, Grieve Records, Cactus Records (now Tandang Records, in Kuala Lumpur) and Slap Bet Records/Vanilla Thunder (Singapore), pitched in together to fund a split 7” single of GHAUST and Kelelawar Malam on colored recycled vinyl with white labels.

The year, however, continued to egg on local music fans as the recently formed record label, Elevation Records, rereleased Jakarta’s alternative act Sajama Cut’s The Osaka Journals – a seminal album for the independent music scene in Indonesia.

People started yearning for the release, or rerelease, of local bands on vinyl, and a niche market began to take form despite the country’s, or even the region’s, lack of infrastructure in pressing the once-forgotten format. There were no pressing plants in South East Asia at that time.

The poster for horror punk band Kelelawar Malam’s vinyl release party in January 2012. (Archive/Grieve Records)

Vinyl for everyone

Pressing vinyl records was, and still is, incredibly tiresome, particularly for independent record labels and bands. It is expensive and involves long lead times for orders, customs uncertainty and, most importantly, the almost-forgotten base knowledge in releasing the format.

As more prominent players scrambled to have their records pressed at plants in Europe and the US, smaller players explored other more peculiar and cheap options – such as lathe-cut records that are physically almost identical to vinyl records yet made with polycarbonate plastic.

In terms of releasing music on vinyl, there was also a learning curve that the local labels and musicians had to go through. David Tarigan from Jakarta independent label and distributor Demajors remembered that people were “sending masters to pressing plants recklessly” during the early days of the resurgence in Indonesia.

The opening of the new pressing plant PHR Pressing, David viewed, would solve this problem for beginners interested in doing a vinyl release. “They’d give advice and directions during every step of the process to yield the best output, from the beginning of the mastering process up until the end. I reckon that they have put together suitable partners, said David.

Clement Arnold, factory director of PHR Pressing, noted that the “lacquers and galvanic [procurement] is still under cooperation with cutting and mastering houses in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. But we plan to provide the galvanic process domestically once everything runs accordingly.” Clement founded PHR Pressing along with Elevation Records in 2023 (announced on April 23), taking over a factory operated in 2019 unbeknownst to the music industry that used Allegro machines, which he noted as a product of a collaboration between M-Tech Engineering and Italy’s MCS Sironi.

Despite not yet having internalized the galvanic process, PHR Pressing is a low-barrier option when compared with manufacturing records abroad, as clients would be spared the headache of dealing with overseas shipping and the sometimes-uncertain customs clearance. “As of now, at least 10 musicians are in line for production,” Clement followed.

Another shift

Currently, a number of labels and artists are pressing their vinyl records in China “or Taiwan,” Herry Sutresna, founder of Grimloc Records, admitted. The quality of their final product proved to be satisfactory, even when compared with plants in the US or Europe.

Grimloc Records, Demajors and Surabaya label Reaping Death Records are three better-known names in the independent scene who press their records in East Asia. But it was not only the advantages that drove the local players to discover pressing plants in the region, a bottleneck in the US and European supply chains was becoming more apparent, especially nearing the end of 2021 when British singer/songwriter Adele’s fourth studio album 30 was scheduled to release.

Sony Music reportedly ordered 500,000 copies of vinyl records of Adele’s 30, causing a significant limiting of production capacity combined with the rolling orders of represses for Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, Queen’s Greatest Hits and Michael Jackson’s Thriller (Billboard’s top 15 most selling albums of 2021).

There was an obvious problem of infrastructure in the vinyl record resurgence. The production capacity of vinyl pressing plants after the shift away from cassettes and CDs could not keep up with the rising trend – hence Jack White’s plea video.

When bands in Indonesia were waiting for their records to be pressed at Gotta Groove Records, US, lead times were at four months (five to six months if including shipping and customs clearance) in 2017, some could even be left waiting for nine months during the 2021 slowdown.

With PHR Pressing establishing its presence with a capacity of 30,000 records per month, as indicated in its release, these numbers become much more meaningful when taken into the context of the shortage, along with its lower barrier of entry. PHR Pressing is the second pressing plant to open in Southeast Asia after Thailand’s Resurrec in October 2019.

Gerry Apriryan, on behalf of music archiving initiative Irama Nusantara, offered an optimistic take on the new plant, hoping that the ease of producing vinyl would lead to the format being perceived as more familiar and ultimately in a more affordable price range. Moreover, Irama Nusantara hopes that more Indonesian albums from the past will be rereleased in the future.

“I think it will change,” said Uri on behalf of Grieve Records, regarding the landscape of physical release in Indonesia. “Two, three years ahead, physical releases in Indonesia could be dominated by vinyl.”

The low barrier offered by PHR Pressing is the main bargaining point, “and the thing that makes me happiest is the fact that there’d be no more dealing with customs.” Uri laughed.

However, some labels have a different perspective on the production price.

Reno Surya from Reaping Death Records and Herry Sutresna from Grimloc Records pointed out that the pricing scheme, at this point, still has some room for improvement. “The [local] vinyl [production] price would still be the same in the future,” said Reno. “Plus, compared with my experience in [pressing] vinyl, the pricing I’ve received [from PHR] can still be said as expensive as importing. When calculated, including shipping and tentative [customs charge and] taxes, it’s still cheaper to import them.”

Yet PHR Pressing will likely go down as a milestone in the history of music in Indonesia, especially in terms of providing a lower barrier service than what the industry has been used to for the past 50 years, exposing more Indonesian artists and labels to the option of releasing their music in the format.

Setting aside the dichotomy of mainstream and sidestream music and leaving out the context of the independent music scene and major players, the resurgence of vinyl records might finally be more apparent for Indonesian artists and music fans.