October 21, 2024

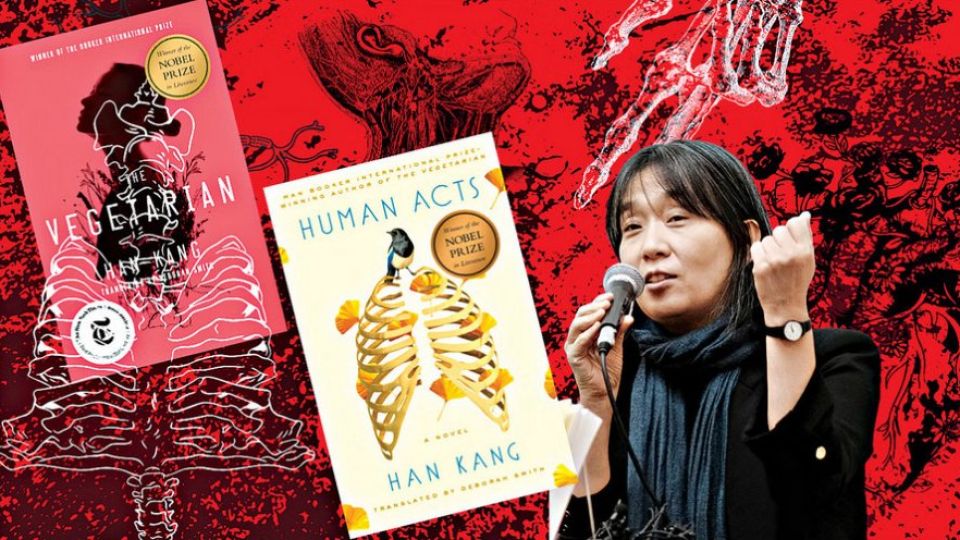

DHAKA – As of writing this article, the official death count in the Palestinian genocide has surpassed 42 thousand lives. In my room, I quietly sit and read excerpts from Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (Portobello Books, 2015) in celebration of her winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. These two events share nothing in common, but they are connected—if only in the loosest sense.

Writers, to me, are either never capable or willing to dive deep into the violence entrenched in our humanity. For sure, many have attempted, but few manage to put the cruelty of our existence so starkly on display. This “humanity” that we are all a part of has led to horrific events, it has led to ongoing genocides and state-sponsored killings everywhere. And when I look at writers addressing the issue, very rarely do I find them succeeding in connecting our history to our grief, to our desire, to transcend it all. This is perhaps why it feels so completely justified for Han Kang’s literature to win such an award in what has been one of the darkest years in our history. This is the perfect time for everyone to sit still and contemplate the nature of cruelty and ask ourselves if that is all that connects us as a species.

Born in Gwangju, a 10-year-old Han had to witness as the South Korean military butchered, raped, and tortured its own people—innocent university students and regular citizens alike—in what became known as the Gwangju Uprising. In her interviews, she has addressed the violence of the massacre and the deafening, outrageous silence that followed in her soft-spoken voice that betrays a wound she has carried ever since. While Human Acts (Portobello, 2016) is perhaps the most explicit demonstration of this wound—her literature is seeped deep into it.

In all four of her books that are currently available in English, Han meditates on grief that comes from the world around us, from the systems that exploit or oppress us, and from our own birth. ‘Aching prose’ is not a phrase I use lightly when I describe her work, and yet even that doesn’t cover exactly how I feel about her words.

The first time I ever read The Vegetarian, I was roughly 16. It’s difficult for me to forget that experience—the extreme violence that hid so neatly under her simple prose. What had this author seen for her to write like this? I wondered. More than that, however, I questioned what the book was really about. Split into three parts, the increasing uncertainty of the narrative filled me with a sense of surreal beauty mixed with dread. By the time the final pages had come along, the book ceased to make any sense to me.

It was only after re-reading it a whole year later that I managed to absorb more meaning out of it. The story of The Vegetarian follows Yeong-hye who, upon having a nightmare of human beings and their cruelty, decides to stop eating meat. The results are devastating for her family and the culture they’ve built for themselves around the consumption of meat. This is the foundation Kang uses to explore the idea of removing oneself from the violence that very much has defined humanity in so many ways. The systems of oppression, the cultural normativity of violence, and the passive ways we all allow them to exist—the book does not attempt to answer questions regarding any of these. If anything, it seems to beg the reader to see and to wonder if this violence is what defines us.

Her poetic style of prose is, again, on full display in The White Book (Portobello Books, 2017) — the collection of poems that work not just as an obituary but as a meditation on the nature of violent grief birthed from innocence lost. It’s a sobering read, and as the story of The White Book chronicles the life of Han in tandem with the death of her sister, I am left with a single question: How does our guilt intertwine with our grief?

At no point in her literature (at least, in the ones that are available in English) does Han Kang attempt to answer the questions she raises, nor does she really find closure to explain her grief away. In many ways, I see this as a resolution within herself. The author cannot answer for humanity’s cruelty, so she carries the grief that comes with it as a reminder. It is only due to these reminders that she is able to meditate, time and again, on the nature of violence that resides in us. In a weird way, I think what she has arrived at is what I would call the true essence of our humanity: hope, despite the terror.

After the news came out of her win, Han Kang took a clear stance in not holding a press conference or celebrating her prize. In her own words, “With the war intensifying and people being carried out dead every day, how can we have a celebration or a press conference?”

Today, the meditations on grief, on histories of violence, and of our tendencies to carry it all with us feel more important than ever. This is not merely a moment of celebration, though it needs to be noted that Han Kang is the first Asian woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. Her win works as a reminder that we must carry on, with the horrors all around us acknowledged and accepted. It is only then that we can fight.