July 30, 2019

A British merchant’s journey from Madras to England that gives a glimpse into early days of colonialism.

“The riches of Bengal…are derived from this river, which with its numerous branches flowing through and intersecting an extensive space of country, transports speedily and at a moderate expense, the various products of districts, towns and villages, to places where they are immediately consumed or collected for the supply of more distant marts. The Ganges also affords a grand aid to the English, in all military operations within their own territory…the Bengal armaments are furnished, from their store boats with every equipment, and the Europeans enjoy, even in their camps, the luxuries of life.”

The importance of the river Ganga — both to Bengal and the British Empire — is just one of the many insights that make up George Forster’s book A Journey from Bengal to England, through the northern part of India, Kashmir, Afghanistan and Persia and into Russia, by the Caspian Sea.

The book, whose first volume was published in Calcutta in 1791, is filled with insightful observations that its author gleaned during a truly unique journey — when he took the overland route from Madras to England.

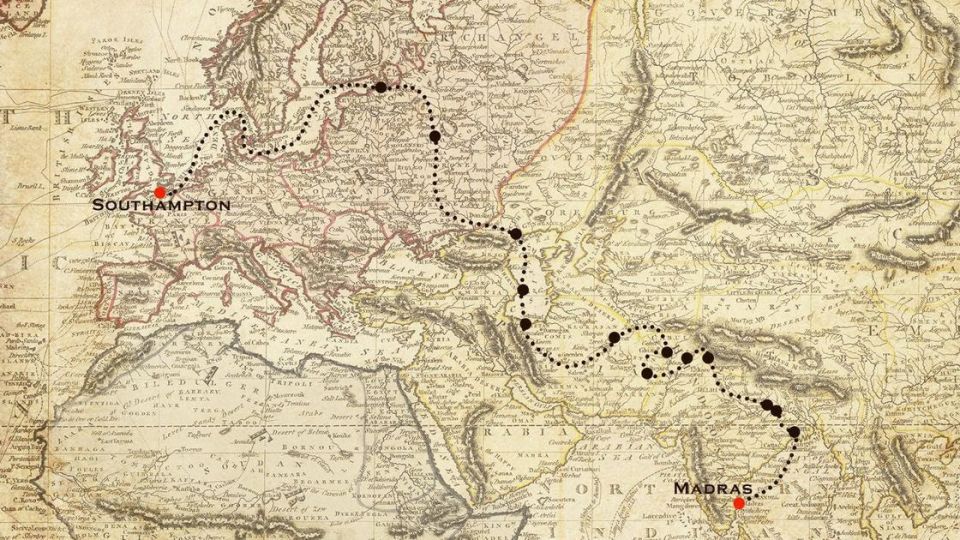

Forster, a merchant in the East India Company, set off on this trek in March 1782. He travelled to Calcutta, moved up the Ganga, and then went by road further north towards Punjab. He then journeyed through Kashmir, Afghanistan and Persia, and crossed the Caspian Sea into the Russian Empire, before sailing to England via the Baltic and North seas.

The documentation of his nearly two-year-long trip shows a keen ethnographer’s interest in the lands he crossed, recording the landscape and detailing a place’s history and its customs in vivid and humorous detail.

Early colonial rule

When Forster began his journey, it was the early days of the East India Company’s domination of India. The Company had started trading in 1600, but by the 1760s, it was in effective control of the three presidency towns of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay. In 1765, it secured the right to collect revenue from Bengal and Bihar.

Elsewhere in India, other powers dominated: the Marathas to the west and north, Hyderabad and Mysore were prominent kingdoms in the south — where the French were a force too — and there were smaller threats like Punjab and the Rohillas in the north.

Travel, in those early days of colonialism, had only just opened. The sea route to England — via the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, with a stopover at St Helena, an island in the mid-Atlantic Ocean — was popular at the time.

To map his route, Forster sought the help of the Orientalist Francis Wilford, who served with the Bengal Engineers, a group that was part of the Company’s Bengal Army. He also familiarised himself with the works of “other Orientalists” in the Company’s service.

Encouraged by Governor General Warren Hastings and philologist William James, officials and scholars were learning languages like Persian and Sanskrit, translating well-known works into English, and trying to understand the customs of the land — all with the help of local Indian assistants.

Safety first

In order to ensure his safety, Forster took several commonsensical precautions. He always travelled in a kafila or caravan of merchants and offered bills of exchange (credit notes) to the merchants who then advanced him money.

He also disguised himself, changing his appearance and name depending on the area he was in. As he advanced up the Ganga into Awadh, he was a Georgian — as British men in the reign of King George III, then the ruling monarch in Britain, were sometimes referred to.

In Kashmir, he became a “Mohammedan merchant”. His disguises became more specific as he travelled west towards Afghanistan and Persia — first becoming a “Kashmiri merchant” and then a Hajji (pilgrim to Mecca). All this helped him blend in and deflect suspicion.

Forster was deeply interested in Hinduism and its myths, beliefs and customs. To satisfy his curiosity, he spent three months in the holy city of Benares. His observations about Hinduism made up a separate book, Sketches of the Mythology and Customs of the Hindus, that was published when he was in London in 1784.

Hinduism, Forster wrote, had started off steeped in simplicity but was later complicated by its priests. He described the holy trinity — the three main gods of the religion — and touched upon the caste system as well.

He found Benaras a crowded city with such narrow lanes that two carriages could not ride alongside. Some houses were five or six storeys high, and the minarets attributed to Aurangzeb towered over the city. Forster soon realised that it was the congestion that was responsible for the perpetual stench that lay over the city.

During his journey, Forster often stopped at caravanserais — a “series of small apartments arranged around a principal gateway” — located every few miles, with provisions for rest, food and water. Most of the “stationary tenants” were women who managed the serais.

They were, Forster writes, very pretty, and they would lay out the bed, fetch a smoking pipe and prepare an adequate “repast” for the guest, his horse and its keeper, for a small sum of money.

Moving north

Though women were conspicuously present in places like serais, Forster observed that “Hindu women” were “conformably in a state of subordination” and it was “judged expedient to debar them from the use of letters”.

On the other hand, “the Hindoo dancing girls, whose occupations are avowedly devoted to public pleasure are…taught the use of letters, and are minutely instructed in the knowledge of every attraction and blandishment, which can operate in communicating the sensual pleasure of love.

These women are not obliged to seek shelter in private haunts, nor are they, on account of their professional conduct, marked with opprobrious stigma.”

Forster’s extensive reading held him in good stead when he travelled through Awadh and Punjab. He had read works on the Sikhs and Shuja-ud-daulah, the shrewd and capable nawab of Awadh, who died in 1775. Shuja-ud-daulah had also been vazir to the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II.

There had always been speculation about Shuja-ud-daulah’s lowly, even infamous, origins. But as Forster discovered from his conversations with merchants and officials in Persia, Shuja-ud-daulah’s lineage went back to a wealthy merchant family from Nishapur in Khorasan, Persia, that had moved to serve the Mughal court in the mid-17th century.

North of Haridwar, the landscape turned “wild and picturesque”. Elephant herds were tracked there and hunted for their tusks. In Kashmir, Forster came across a shop where kebabs and beefsteaks were being prepared and conversation was flowing easily, reminiscent of the coffee houses in London.

As he travelled northwards, the weather grew colder, but Forster remained unaffected — humorously attributing his resilience to his habit of “smoking tobacco”.

Rich legacy

Forster was enchanted with Kashmir and described it as “unparalleled for its air, soil and picturesque variety of landscape”.

The beauty of Kashmir was nearly forgotten when he had to endure an agonising camel ride through Afghanistan while sharing a pannier with a woman and a wailing baby.

In Kabul, he witnessed a “common toleration of religion” — “Christians, Jews and Hindus openly professed their religion and pursued their occupation without molestation”. Herat, he saw, had a thriving community of Hindu merchants.

In Persia, he travelled through places such as Khorasan, Mazendaren and then Mushid-sir, south of the Caspian. From there, Forster sailed with some Russian merchants to Baku, which at that time was part of the Russian Empire.

After nearly 22 months on the road, he finally reached Moscow in March 1784. Three weeks later, he was welcomed by the British consul in St Petersburg, then the Russian capital. It did not take him long after that to sail via the Baltic and North seas to reach Southampton in England.

Forster returned to India in 1785. His knowledge of Marathi and his autodidactic skills as an ethnographer and sociologist made him invaluable to the East India Company. Lord Cornwallis, as the Company’s governor general, deputed him to interact and negotiate with the Bhonsles, the Maratha rulers in Nagpur.

Forster, along with another Company official James, Nathaniel Rind, surveyed the route from Calcutta to Cuttack, in Odisha, a Maratha stronghold that the British were eyeing.

But just as Forster was beginning to distinguish himself as a diplomat, as someone able to conciliate between rivals and yet advance the Company’s position at an uncertain juncture in Indian history, he died an untimely death, at the age of 39, in Nagpur.

Forster’s descriptions helped the surveyor Major James Rennell — who had already produced maps of Bengal and the Ganga river — in his magisterial 1788 work Memoirs of a Map of Hindustan; or the Moghul Empire. The second volume of Forster’s memoirs was published in 1798 along with another edition of the first volume.

These works were soon translated into French and German and showed how Forster’s detailed observations were valued at a time when the East aroused curiosity, yet remained mysterious.

!['Dusaswumedh Ghat, Benares', a lithograph by James Prinsep. Image credit: James Prinsep, British Library/Wikimedia Commons [Licensed under CC BY Public Domain Mark 1.0].](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2019/07/5d3eda0d58be8.jpg?0.37689726255255374)

!['Hindu Dancing Girls'. Image credit: Allan Newton Scott/Wikimedia Commons [Licensed under CC BY Public Domain Mark 1.0].](https://i.dawn.com/primary/2019/07/5d3eda0cd6a3a.jpg)