August 1, 2023

Politicians and rulers, whether of the more democratic dispensation or otherwise, have a habit of going out of favour with the status quo. When that happens, every attempt is made to malign their character and delegitimise their narrative in the eyes of the public, whether by highlighting their misdeeds or by completely wiping them from the mainstream narrative.

The act of erasing or tainting the memory of a political opponent has been happening for eons. Damnatio memoriae, a latin phenomenon that literally translates to ‘condemnation of memory’, refers to a loosely defined group of processes, which involve destruction, erasure, and silence. These processes are also understood as “memory sanctions”.

For the last several months, PTI leaders, especially former prime minister Imran Khan, have found themselves out of favour with the powers that be. That the former premier has chosen to up the ante and indirectly, and at times directly, accuse the military establishment for his political misfortunes hasn’t helped their cause either.

What has followed can be described as the ‘damnatio memoriae’ of Imran — a barrage of legal cases against him and other party leaders, swift reprisal for anyone speaking out in his favour and a near-complete blackout of the former premier from the mainstream media. In fact, at one point, even popular video streaming platform, YouTube was temporarily — albeit unofficially — suspended at the time of Imran’s live speech to stop him from addressing his supporters.

Perhaps the most literal example of this attempt to erase Imran is when private television channel ARY earlier this month came under fire for blurring out his image during a live broadcast of the party leaders’ meeting with IMF officials. The move sparked several trends on Twitter, where users ridiculed the TV channel’s attempt at censoring a former premier.

Veteran cricket legend Javed Miandad also took to Twitter to mock the censorship attempt. “If Pakistan wins [the] World Cup in this government, a suggested post …,” he wrote.

This isn’t the first attempt at muzzling the former premier either.

Last year, on August 21, the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra) imposed a ban on the live coverage of Imran’s speeches. The move had come after Imran allegedly threatened a judge and police officers over the custody of Shahbaz Gill, a former aide to the ex-prime minister.

However, Imran challenged the ban and approached the Islamabad High Court (IHC), which on September 6, 2022, overturned the ban, allowing live coverage of Imran’s speeches to resume.

Two months later, on November 5, Pemra again slapped a ban on Imran’s press conferences, which was yet again lifted hours later, with Information Minister Marriyum Aurangzeb saying that the incumbent government believed in “democratic principles and constitutional freedoms of expression”.

In spite of that, on March 5, 2023, Pemra once again imposed a ban on the broadcasting and rebroadcasting of Imran’s speeches and press talks on all satellite TV channels. This action was taken after the former premier criticised government leaders, accusing them of keeping their wealth overseas and receiving legal protection from former army chief Gen (retd) Qamar Javed Bajwa.

In a prohibition order, Pemra instructed all licensees to avoid broadcasting “any content against state institutions”.

With all these attempts to block the former premier from mainstream media, Imran has joined the list of political leaders, including Altaf Hussain, Nawaz Sharif, and Maryam Nawaz, who have previously undergone or are currently experiencing a similar fate.

It is important to note that during Imran’s own tenure, opposition politicians’ interviews and press conferences were frequently censored or silenced. Their crackdown on the freedom of press was also no hidden fact, with the introduction of draconian laws such as the PMDA Ordinance and Peca Amendment Ordinance.

However, now that the tide has turned, the PTI chief himself has become a target of the same censorship mechanism.

But if you think Pakistan is an anomaly here or that political leaders here are the only ones attempting to wipe out each other from cognitive memory, you couldn’t be more wrong.

Tracing it back to the Egyptians

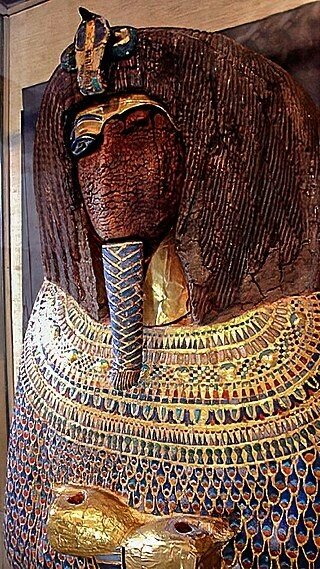

The practice, in fact, dates back to the ancient Egyptians, evident in artefacts from pharaoh Akhenaten’s tomb. Instead of worshiping gods of the traditional pantheon, Akhenaten’s sole devotion to the god Aten was considered heretical.

Coffin from KV55 in the Valley of the Kings has face and the cartouche containing the name of the occupant defaced in ancient times. — Hans Ollermann

The people blamed their misfortunes on Akhenaten’s shift to Atenism from their former gods. After the pharaoh’s reign was over, god Aten’s temples were dismantled, using their stones for new constructions. Akhenaten’s depictions were defaced, while references to Amun, previously chipped away and removed by the ruler, reemerged.

The Romans did it too

Similarly, the Romans had a tradition of emperors removing the traces of former rulers. The term damnatio memoriae was also coined during this era.

However, these attempts were never fully successful. For instance, in the case of Emperor Geta, it proved challenging to completely eliminate coins featuring his likeness from circulation for several years, despite the severe penalty of death for merely uttering his name.

The image, with Geta’s face removed, can be found at the Altes Museum in Berlin. — Carole Raddato

Scholars agree that the act of erasure itself contributes to the memory of that person, often elevating them to the status of martyrs. Moreover, attempts by historians to revive the memory of any individual cannot be halted in the future.

Soviets and the advent of photography

Despite its futility, regimes in power still continue to do it. After the dawn of photography, the Soviet Russia frequently used editing to remove individuals, who were once allies and later fell out of favour, from photographs of Lenin and Stalin.

For instance, on May 5, 1920, Lenin gave a famous speech to the Red Army at Sverdlov Square in Moscow before their departure to the Polish front to fight against Josef Pilsudski’s troops. Leon Trotsky and Lev Kamenev were present in the foreground.

In the initial photograph, Trotsky and Kamenev were depicted near the staircase, but they were subsequently removed from the image.

— Mansell / Time Life Pictures / Getty

According to the TIME magazine, “though the [original] photograph was widely published with the two men present during the 1920s, it was reproduced with stairs in their place for most of the Soviet era, even during the Gorbachev period.”

Soviet Russia’s Stalin was infamous for manipulating pictures with individuals who were once close to him. One such instance is when a photograph showed Nikolai Antipov, Stalin, Sergei Kirov, Nikolai Shvernik and Nikolay Komarov. In the subsequent edits of the same pictures, one after the other, every person was removed, leaving only Stalin.

— Wikimedia Commons

It is important to note that it is unclear whether all of these people were removed from the photograph because they “fell out of favour” with the Soviet leader.

However, that is not to say that the Soviet imagery was never amended to alter the narratives of history at many instances. More often than not, these attempts to remove people from any form of documentation were done without any explicit policy.

In David King’s The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, the photography expert explores how during The Great Purges of the late 1930s, Stalin’s former defendants and political enemies were killed and subsequently removed from photographs and visual records.

The defacing didn’t stop at the state level, but also resulted in people defacing their own materials to not be deemed “anti-Soviet” or “counterrevolutionary”.

The act of self-censorship has also been prevalent across time and regions. Even with ‘official’ orders, people — particularly the press and media — tend to take measures to avoid getting in trouble with the authorities.

When regimes change

Another manifestation of damnatio memoriae can be observed during a complete regime change, where efforts are made to distance the new hegemonic class and systems from the previous regime. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ukraine saw the era of “decommunisation” where laws sought to erase and ban Communist symbols in the country. In less than a year, more than 100 Lenin statues were reportedly dismantled after the overthrow of the pro-Russian government in 2013.

A 50 year old statue of Lenin was toppled down by Ukrainian Nationalists in the eastern city of Kharkiv in 2014. — AP

Similarly, following the US invasion of Baghdad in 2003, a statue of Saddam Hussein, the former President of Iraq, was brought down.

A US soldier watched as a statue of Iraq’s President Saddam Hussein was taken down in central Baghdad, 2003. — Reuters/Goran Tomasevic

The act of removing statues and symbols associated with former powerful figures is a widespread phenomenon globally. In the wake of the 2020’s ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests in the US, there has been a surge of demands and commitments to dismantle statues honouring slave-owners and traders in both the US and the UK.

This exemplifies how societies undergo a collective shift in their perspective, seeking to dissociate themselves from a troubling historical legacy. Erasure becomes a way to redefine national and cultural memory.

Anti-racism protesters across the US and UK called for the take down of historical figures engaged in slavery. — Reuters

“Today, as people take to the streets to demand the removal of public statues, names on buildings, and commemorative plaques, these calls for damnatio memoriae are not acts of erasure — they are not about forgetting the past or striking individuals from our history,” wrote Mati Davis and Sara Chopra in an article, ‘Damnatio Memoriae: On Facing, Not Forgetting, Our Past’ published in a UPenn Classical Studies Publication, DISCENTES.

“Rather, they are acts of creation, attempts to redefine our perceptions as a twenty-first century society,” they added.

Our legacy

So how have these attempts at redefining perceptions been applied at the local level?

During the regime of Chief Martial Law Administrator General Yahya Khan, for example, there was a commitment to assemble the Constituent Assembly and draft a constitution, ultimately transferring power to the majority party elected. After the elections, however, when it became apparent that the Awami League had secured a decisive victory, apprehension arose within the establishment regarding the potential weakening of central authority if the League’s six-point agenda were to form the basis of the Constitution.

In his book Media, Religion, and Politics in Pakistan, Rai Shakil Akhtar describes how the mainstream media based in West Pakistan reflected the sentiments of the status quo group and the political force of change — led by Gen Yahya and ZA Bhutto.

“The media treatment of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the leader of the majority party, is couched in negative vocabulary. He is projected as an ‘intransigent’ and ‘obstinate’ person,” Akhtar noted after analysing news coverage of Mujib in various mainstream newspapers.

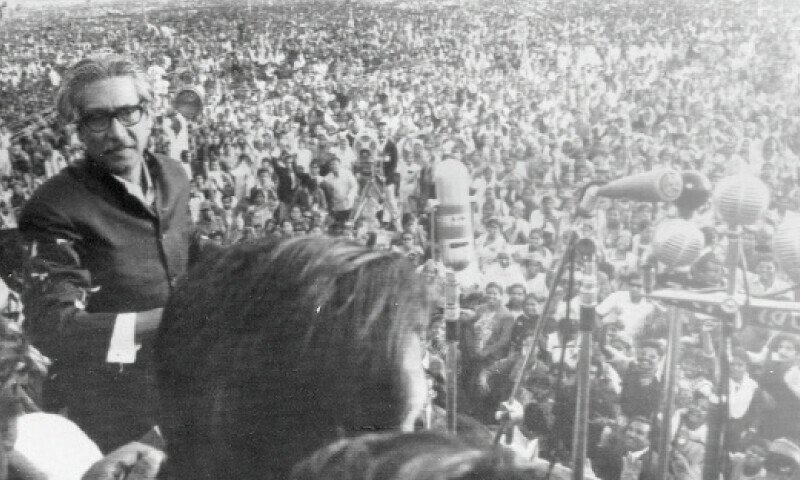

Sheikh Mujibur Rehman approaches microphones to address a rally in Dhaka. — File

Although Mujib’s presence in collective memory remained, it was apparent that deliberate attempts were made to manipulate his reputation and shape the collective perception of him.

It is indeed ironic that, around a decade later, during General Zia’s military dictatorship, news coverage concerning Bhutto’s family members faced stringent prohibitions. This period coincided with the dictator’s ban on all political activities in the country.

A picture of the Bhuttos taken during a family excursion shows (from right to left) former PM Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, his wife Nusrat, daughter Sanam, son Mir Murtaza, daughter Benazir and son Shahnawaz. — DAWN

A senior journalist told Dawn.com that during Gen Zia’s era, newspapers weren’t allowed to publish photographs of former PM Benazir Bhutto. He pointed out that such dictations from the state are — more often than not — unofficial policies and therefore, no records exist of such bans.

In their historical study, “Freedom of Expression and Media Censorship in Pakistan,” Saima Parveen and Muhammad Nawaz Bhatti found that the “media was duly so much bound to obey the government that, Pakistan Television was not allowed to show a single shot of Benazir Bhutto, except once for a couple of seconds, from July 1977 when General Zia-ul-Haq imposed Martial Law up to August 1988 when he died in an air crash.

“For eleven years whereas the General appeared every single day, she was kept away from TV and Radio.”

When The Star covered veteran TV anchor and bureaucrat Mahtab Rashdi’s wedding, they printed a huge photograph of Benazir with the bride. The caption said, ‘The bride with a guest’. As a result, the popular newspaper was taken off the stands and the editor at the time, GN Mansuri, had to stay underground for some time.

A modern touch

Despite Pakistan having democratically elected governments in place since 2008, the practice of “unpersoning” influential individuals who no longer align with the established order persists.

Over the last decade, politicians have routinely gagged their opponents who have fallen out of favour — and power — be it Maryam Nawaz, Nawaz Sharif or Altaf Hussain, who were all censored, whether officially through Pemra, or through unofficial channels.

The same methods of censorship were again applied against the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), which took to the streets in April 2021, calling upon the government to fulfil the demands agreed upon during their previous protest. Soon after, Saad Rizvi, the far-right group’s new leader, was arrested.

Police use tear gas to disperse supporters of Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) during a protest in Lahore in April, 2021. — AFP

Clashes erupted across cities and the government declared it a proscribed entity under the anti-terrorism law. Subsequently, Pemra also banned the television and radio coverage of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP).

The government even declared TLP as a proscribed organisation for “being engaged in acts of terrorism, [and] acting in a manner prejudicial to the peace and security of the country.”

However, the first time the TLP had appeared on the national stage with a thousands-strong rally, followed by a sit-in at the now infamous Faizabad Interchange in 2017, the media had “provided unabated coverage”.

“The free publicity made TLP, a little known political party, into a phenomenon. Basking in the limelight, TLP’s leadership became ever more intransigent, abusive and aggressive,” Justice Qazi Faez Isa had observed in the Faizabad Dharna case.

Four years on, with the TLP seemingly no longer in good graces as it once was, the media hardly paid it any attention, to the extent one would think there was no protest taking place — that is until the violence had gripped several cities across the country and resulted in several deaths.

Coming back to one of the most popular — if not the most popular — national political parties right now, the PTI finds itself in a quandary. Many of the methods tested and used time and again are being applied to silence its leaders in order to remove their narrative from national consciousness.

With social media being the all-time spoiler in this game of erasure, it remains to be seen how this plays out — whether the PTI and its leaders will forever be annulled from the annals of history or whether they would be able to persevere and ultimately, be allowed on the airwaves again.