September 26, 2024

MANILA – Whenever we tell our students to keep on fighting for the poor and oppressed, they often feel dwarfed by the magnitude of the problem of poverty.

And rightly so: millions of Filipino families are hungry; a third of our children is stunted; millions of people are reliant on dole-outs because they are under-educated and therefore unqualified for employment; and so many focus on survival so that they make decisions that can put them in danger, whether it’s in the places they live or the people they vote for.

Even donated food (sardines, instant noodles) puts the poor in harm’s way, whether they are adults who need to stay healthy or children with developing brains. Their diets cannot help them grow into a population that participates in the economy and speaks up in a democracy. Their diets cannot help them improve their lives if there are no enabling mechanisms in place.

People aren’t just hungry; they’re hungry for a world where they can improve themselves to get out of poverty, but they can’t do that if their stomachs are empty. It’s something that Fr. Ben Nebres always talks about when he shares how and why he organized the Ateneo Center for Educational Development (ACED), which seeks to improve public school education. I sat with him over lunch at the Jesuit Residences, following my column a few weeks before that featured him and his work. There were updates on ACED’s programs, he said, and he wanted to discuss them with me.

Seeing Father Ben talk about helping the poor is like seeing a child excited about a project that keeps on giving. He made the ACED story more real, the same way that helping out in packing vegetables, giving food to parents, or serving poor, young students would make anyone feel that they were truly contributing to a greater cause, rather than simply handing money over.

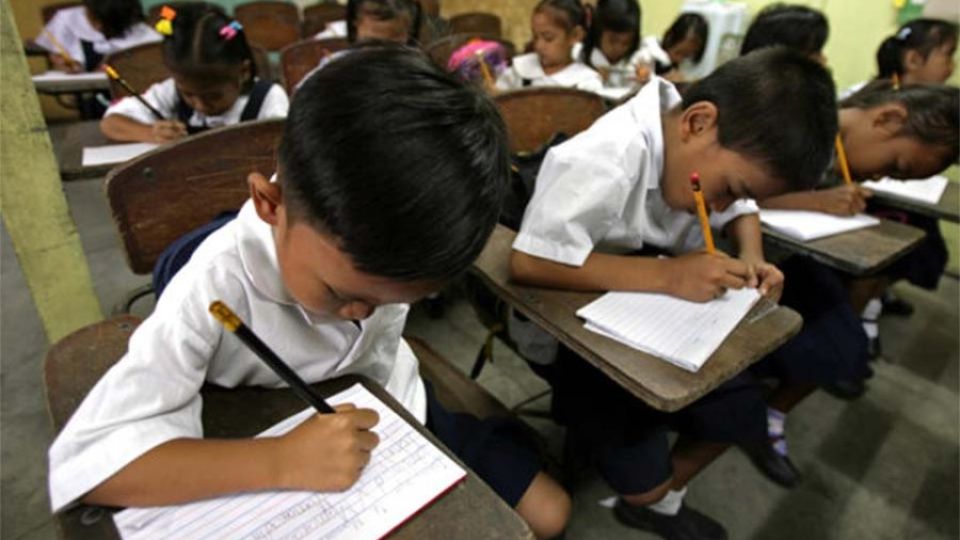

There were no abstract theology or political science lessons. There was, however, real defiance, against an economic system that had allowed so many people to go hungry—against a social system that has put so little value on genuine empathy. ACED began with teacher training before Father Ben moved to directly target students who couldn’t go to school because they were hungry, or were teased for being dumb but really couldn’t see properly. Father Ben solicited the help of the private sector, and various foundations came to his aid as he sought a holistic approach to improve public school education.

At the center was a good meal: fresh produce from nearby farms that would help farmers earn their keep, soup kitchens that would make hot meals that students could either pick up at school or bring home, food that was made and served immediately minus preservatives.

Not even the pandemic stopped their work. ACED distributed food through schools when parents picked up their children’s modules. Their efforts allowed farmers to continue earning money, and out-of-work volunteers to make a living through deliveries. Even Marawi, once battered and broken, now has programs spearheaded by ACED and its partners to feed and educate children post-war.

Today, the work of ACED has branched into teaching children how to read, and by reaching out to tutors who can assist those who need help the most. The program has fed over a hundred thousand students in a variety of towns across the archipelago, a tiny fraction of the millions of children still hungry.

And yet no task seems daunting for Father Ben, who speaks youthfully despite his thin strands of silver hair and his cane to help him walk. It’s as though he’s always ready to spring out of his seat, to ask corporations for help, check on the children participating in the program, or travel to the many places where the poor still wait with their empty plates.

He still teaches, and he always invites our students to help out. The easiest way is for students to participate in packing vegetables that are delivered to the campus: in a corner tucked away among the trees is the ACED packing site, where tons of produce and rice come each day, waiting to be assembled into bags to be sent to the kitchens. Even one extra pair of hands can speed up the work.

Our students feel overwhelmed by the world’s problems, but perhaps they need to step away from the notion that they, alone, are tasked to change the world. Connections have to be made: farmers, corporations, teachers, and parents all come together; a community must already be organized into networks of cooperation and aid so that such feeding programs can flourish.

Not everything has to be built from the ground up, and not all fights begin with weapons. There, too, is space to fight against systems that keep the poor hungry and desperate.

Such a fight might mean giving money; but to truly reach out to those whom we fight for, the battle can be fought by filling up a child’s plate. It can be on site in the darkest corners of our cities. It can be under the shade of trees, as one fills up a bag with fresh food that will allow a child to see tomorrow.