December 1, 2023

TAHARA, Aichi — Donald Keene, who introduced the charms of Japanese literature to the world, in his later years published a book about Watanabe Kazan (1793-1841).

A painter in the late Edo period (1603-1867) and a retainer of the Tahara clan, which presided over present-day Tahara, Aichi Prefecture, Kazan tragically ended his life under the strong influence of the time when the country was about to open its borders to the outside world after 300 years of isolation.

What attracted Keene to Kazan?

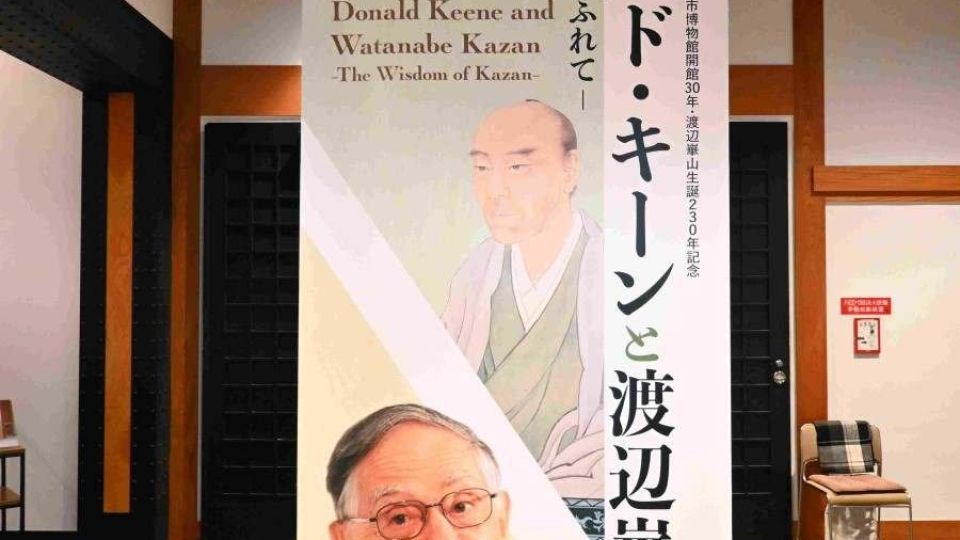

I visited the Donald Keene and Watanabe Kazan exhibition being held at the Tahara Municipal Museum, which is open through Sunday.

The museum is located at the ruins of Tahara Castle, a structure with architecture reminiscent of the time when the castle was built. The museum opened in 1993, and the current exhibit is a special exhibition celebrating the 30th anniversary of the museum. Keene served as the museum’s honorary director from 2017 to 2019, when he passed away.

Kazan showed his talent as a painter in the pursuit of realism. He painted many portraits that captured the individuality of people in a realistic manner, as well as works that depicted everyday scenes of common people in the Edo period. His works are highly valued to this day.

Kazan was also interested in Western knowledge, including practical matters during Japan’s period of seclusion. He compared the superiority of Western studies with Confucianism brought from China, which at the time was the standard of learning for the samurai class, and believed that if one was obsessed with conceptual studies, one was a “frog in a well” and that national defense was at risk.

Such thinking was regarded as criticism of the Tokugawa shogunate, and Kazan was arrested in 1839 and put under house arrest at his clan estate in Tahara, far from the Tahara clan residence in Edo, present-day Tokyo, where he was born and raised. In 1841, Kazan committed suicide at his home in Tahara

Keene, who died at the age of 96, wrote a series of reviews about Kazan in magazines, followed by the publication of a book titled “Watanabe Kazan” in English in 2006 and in Japanese the following year. However, his encounter with Kazan goes back half a century earlier.

According to Keene’s book, the link traced back to two illustrations in “The Western World and Japan” published in 1949 by the British diplomat and historian George Sansom. One of the illustrations, drawn by Kazan, depicted Kazan with his hands tied behind his back while being interrogated by two samurai. Keene wrote that the work showed how harshly Kazan had been treated after his arrest for being too partial to the West.

As such, the most significant feature of the exhibition is that the book’s descriptions are arranged alongside the works by Kazan that appear in Keene’s book and are notated with Keene’s opinion of the artist. For example, next to the “Isso-hyakutai Zu” drawings that depict the lives of Edo people, including a goldfish merchant, Keene praises the work, saying that he could think of no other pieces that so vividly and effectively illustrate the lives of the people in the capital.

“I think Keene-san was very sympathetic toward Kazan,” said Yosuke Kimura, a curator who showed me around the exhibit while talking about Keene’s interest in Kazan and his motivation for compiling his writings into a book. Kimura continued by quoting Junichiro Tanizaki, an iconic writer from the late Meiji (1868-1912) into the Showa (1926-89) eras, who wrote that Keene studied and introduced Japanese literature with a firm foundation and knowledge of Western civilization, which is why it spread throughout the world and also influenced the Japanese people.

“Kazan was an honor student who was educated in Confucianism and studied with some of the leading Confucian scholars of his time. With this as his base, he started studying Western knowledge,” Kimura said. “I think Keene-san saw himself in Kazan.”