June 23, 2022

SEOUL – A police officer in South Korea is awaiting punishment after he lost his bullet holder with six rounds of ammunition in it on May 18.

The incident, belatedly revealed to the media, made headlines, as he belonged to a special police unit in charge of security services for the office of President Yoon Suk-yeol in Yongsan-gu, Seoul. Criticism ensued over the police’s lax management of firearms and slack discipline.

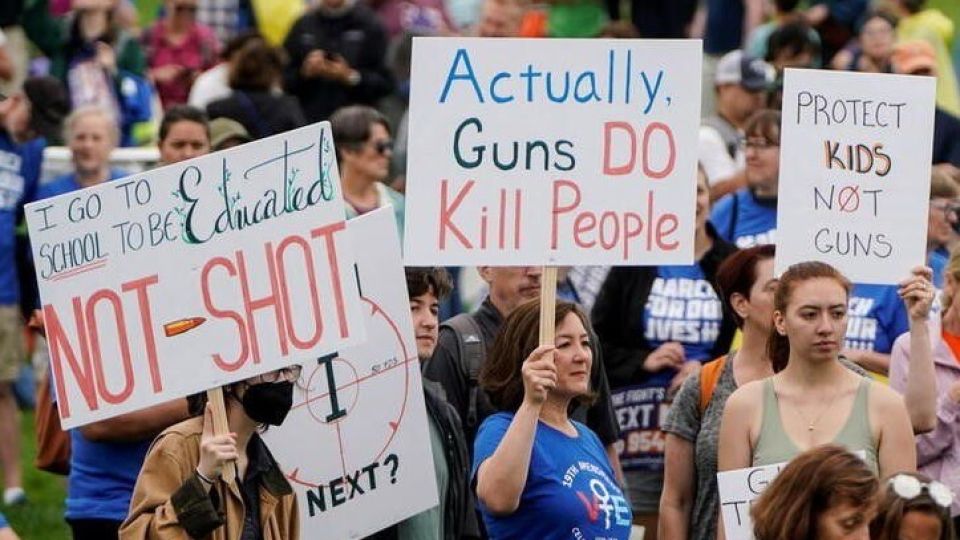

In the aftermath of the event, the unit’s leader was replaced on Wednesday. This, perhaps, is one of the examples that demonstrate how different Korea and the US are when it comes to gun control.

Gun violence rare in Korea

Most South Korean men are trained shooters, having gone through mandatory military duty. But due to a strict gun control policy, there have been no deadly shooting rampages here, as seen in the US.

The most recent case that could be described as gun violence was the fatal shooting in April of a taxi driver who was urinating near the mountain Bukhansan in Seoul by a registered hunter who mistook him for a wild boar.

“Why was the hunter allowed to use a gun in the middle of a city? No civilians should be allowed,” read a comment to an online news article. Other comments requested the government to tighten the hunting license system and better protect citizens.

According to local laws on the safety management of guns, swords and explosives, only authorized personnel in security-related fields, including police officers, soldiers and security guards protecting government figures or foreign delegates can be in possession of firearms.

Shooting athletes, manufacturers and sellers of firearms, those who need them for construction works or as a prop in movies or plays can get gun permits.

Other than them, only licensed hunters are allowed to carry a gun.

There were about 35,000 hunters who passed the rigorous qualification process and now possess a hunting rifle, according to government data from 2021.

The 10-step process involves completing two major requirements — a hunting license and a gun ownership permit.

An applicant must take a state-authorized written test, followed by training sessions at authorized shooting ranges or other institutions designated by the government.

Those who get through them are required to take a medical checkup at a general hospital to verify that they do not have any disqualifying conditions. Mental or drug-related issues will deprive the applicant of access to guns.

Next, they need to get a gun ownership permit that is issued by the police.

Even after purchasing a gun from local dealers, hunters are banned from keeping the gun at home. Except during the hunting season in Korea, which usually falls between Nov. 1 and Feb. 28, they are required to keep it at a police station.

Police officers patrol around the presidential office in Yongsan-gu, Seoul, on May 22. (Yonhap)

Police guns just for show?

Koreans think of guns as something that only police officers or soldiers can handle.

But even police officers have limited access to guns.

Police officers can carry a gun only when they are on patrol, are dispatched to respond to a report or when guarding important government officials.

Once they return to their base, they are obliged to place the gun and bullets at a top-security storage space within the police station.

The law allows police officers to use firearms to protect citizens and themselves, but in practice, they rarely use their weapons. Even when police are called to the scene to respond to a violent crime, civilians are generally not expected to carry guns, so the use of a lethal weapon by officers tend to face major scrutiny for it to be justified.

A 43-year-old police officer at Seoul Hyehwa Police Station’s guard division said officers are reluctant to use guns.

“When it comes to the gun use, many of us fear that lawsuits may be filed by suspects who get shot. Also, past cases where police officers were disciplined for firing the service weapon have made us prefer tear gas guns or stun guns instead,” the officer surnamed Yeom told The Korea Herald.

A study released in April by a joint research team from Dongseo University and Hansei University this year backed Yeom’s views.

The findings of the study, which was based on interviews of 25 police officers working in Incheon, showed officers were reluctant to pull the trigger because of “negative news and public opinions about the police use of force,” “civilian complaints,” “prospects of legal troubles” and “fear of disciplinary measures.”

Bullet shells (123rf)

Soldiers comb ground for bullet shells

Soldiers in the country’s armed forces are also subject to strict firearm control measures.

All soldiers are required to collect their empty cartridges after each rifle drill. One spent shell means a soldier has fired a shot.

The practice of keeping track of every shot fired is aimed at “reducing risks of accidents caused by concealment of live ammunition,” an official at the Defense Ministry said.

“If a soldier loses a bullet, he should submit an excuse letter to the unit in charge of managing firearms. He won’t be punished, but his commanding officer’s reputation is likely to be damaged,” he said.

Loopholes remain

Despite the tough oversight of firearms, there still is a black market for firearms.

Between 2018 and June last year, there were a total of 138 illegal transactions of firearms, according to Rep. Park Wan-soo of the ruling People Power Party who cited data from the National Police Agency.

An NPA official said some of them may have been smuggled into the country.

“We can’t exclude the possibility that some may have come from American forces stationed in Korea. There could be various illegal channels,” the official said. A 2009 report by local broadcaster SBS shows police confiscating a cache of military items held by an illegal dealer in Seoul, which include firearms with “Property of US Government” written on them.

More recently in 2017, a man was arrested for attempting to rob a bank with a gun, which police assumed to be a remnant of the 1950-53 Korean War. He reportedly found the weapon in a cellar of an acquaintance more than 10 years ago.

Every year since 1972, the Korean police run a nationwide campaign to encourage those who own guns illegally to voluntarily turn them in. The monthlong campaign is held twice a year, in April and in September.

During this period, police don’t ask where they got the weapons and do not pursue criminal charges. Under the current law, the illegal manufacture, sale or possession of firearms is punishable by imprisonment of up to 15 years or a fine of up to 100 million won ($77,400).