September 25, 2024

BEIJING – Editor’s note: Traditional arts and crafts are supreme examples of Chinese cultural heritage. China Daily is publishing this series to show how master artisans are using dedication and innovation to inject new life into heritage. In this installment, we explore the long-lasting luster of lacquer.

Related: Lacquer art: Tears of nature, timeless beauty

Art form utilizes nature’s resilient sap and evolves with the accumulation of time, patience and artistry, Lin Qi reports.

At first, it appears to just be a piece of decayed wood. No one would bother giving it a second glimpse. Not unless one is told that this object, standing no more than 6 centimeters with some red stains, is of great historical significance. Belonging to the Neolithic period, it suggests that people living along the Yangtze River between 6 and 7 millennia ago had sourced sap from lacquer trees and used it to facilitate their daily lives.

This wooden piece, later identified as a bowl coated with a thin layer of lacquer, was excavated from the relic site of Hemudu Culture in Yuyao, Zhejiang province, in 1977. The Neolithic culture once thrived along the Yangtze’s lower reaches and, according to archaeological findings, has produced jade objects, lacquerware and other relics.

When the people of Hemudu applied lacquer to the bowl, it is believed that they also mixed the varnish with vermilion to beautify the piece, explaining the red stains.

The bowl is now part of a collection at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in the provincial capital of Hangzhou.

Lacquer art is widely applied in the making of various items, such as vases. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

The chemistry between a man’s hands and raw lacquer evolved in this land for millennia.

The advances of human intelligence to utilize the juice of nature, manual dexterity and creativity have dramatically changed the appearance of lacquerwork. It is vividly evident if the Hemudu bowl is juxtaposed with another bowl, made by prominent living artists in the field, such as Gan Erke, 69, from Anhui province, who is reputed for his lacquerwork featuring distinctive marbled patterns.

No one could better summarize the evolution of the techniques and artistic styles than Yang Ming, a celebrated lacquerer of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), who wrote in the preface for Xiushi Lu, a publication on Chinese lacquerwork written by fellow artisan Huang Cheng in the 16th century, which stated that the techniques and types “have been so well-developed and diverse, one would find it an extravagant feast for the eyes”.

Lacquer art is widely applied in the making of various items, such as ornamental boxes. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

Depth of layers

Archaeological work has revealed that people began to use the fluid from lacquer trees as early as 8,000 years ago. “Because of its fine physical and chemical properties, natural lacquer as a coating material played a vital role in ancient times,” says Yang Peizhang, 47, a lacquer artist and associate professor at the Academy of Arts and Design, Tsinghua University, in Beijing.

He is referring to a lacquer bow found at a grave site of the Neolithic Kuahuqiao Culture in Hangzhou, which is over 1,000 years older than the Hemudu bowl, and therefore considered the earliest lacquer object found in the country.

Lacquer sap was one of the early gifts people received from nature. It is milky and grayish when collected, and as it is exposed to the air, it turns a dark brown color.

After being purified, the lacquer is ready for use. It protects objects from water, humidity and insect infestation so they are more durable. It can also be mixed with color pigments for decorative purposes.

Yang Peizhang, 47, an artist and associate professor of Tsinghua University. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

Layering lacquer onto the surfaces of objects multiple times for better protection requires patience; each layer must dry before the next is added. The process results in a distinguished depth, which is smooth, shiny and mysterious, leaving the object in a state of stability — achieving aesthetic heights that Yang Peizhang describes as “an essential part of the Eastern cultural tradition”.

This was grounded on a system of sophisticated workmanship gradually formed in practice by craftsmen throughout several millennia, he says.

At Phoenix Kingdoms, an ongoing exhibition at the National Museum of China in Beijing, one will feel the splendor of lacquerwork in the late stage of the Bronze Age, proceeding people’s initial exploration with the material and craft in the Neolithic period.

Lacquer art is widely applied in the making of various items, such as bowls. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

From the collections of five museums in Hubei province, a production hub of lacquer trees, a wide variety of objects on show stand as witness to the flourishing of several states between the 11th and 3rd centuries BC.

“Lacquer, lightweight and accessible, was used in many aspects of life at the time,” says Chen Keshuang, the exhibition’s curator.

“It was applied, mostly on a wooden core, to make armors, vessels, plucked zithers, wine cups, ornamental objects and drums.”

These pieces are testimony to the height of lacquerware that would run through the 3rd century. Striking visual effects were created on an opaque lacquer-coated surface on a wooden, metal, cotton or other type of core, such as outlined patterns with other pigments, inlaid fine shells to generate light contrasts, and carved relief patterns — and sometimes gold leaf filling — to exhibit a three-dimensional effect.

A lacquer deer on display at the Beijing exhibition Phoenix Kingdoms. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

Popular decorative motifs included animals, clouds and geometrical shapes.

This was just the beginning of ancient Chinese utilizing lacquer and other materials to make wares that define timeless beauty in their living spaces. By the time lacquerers Yang Ming and Huang worked on Xiushi Lu, there had been 14 primary crafts and over 300 varieties of lacquerware.

In the book, Huang mentions one such sophisticated technique called xipi qi, in which the time-consuming process of coloring, layering and polishing ultimately assumes a dazzling pattern — multiple interlaced colors, predominantly red, yellow and black, sometimes added with other hues to present “a harmonious feeling, and with a closer look, changeable details, a sense of fluidity and splendid luster”, as the late scholar Yuan Quanyou once described.

Cai Shuikuang (1939-2021), a master artisan in Fujian province. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

Diverse styles

Gan, an esteemed artist committed to carrying on this unique lacquer style into modern times, says there is a debate over how the term xipi originated — it could be inspired by a torn leather saddle or the texture of rhinoceros hide — while “it is agreed that lacquerers discovered the color patterns in nature and managed to replicate them on lacquer”.

He says the encyclopedic view of Chinese lacquerwork shows varying features from different regions to reflect local history and cultures, as “some developed a neat, majestic style to fulfill royal requests while others addressed the aesthetic preference of intellectuals to be poetic and aloof”.

In the mid-17th century, artisans in southern Fujian province developed a new technique to decorate Buddhist statues with lacquer threads, which further evolved into a homegrown form of lacquered sculpture. When Cai Shuikuang (1939-2021), a lacquerer in Xiamen, Fujian, inherited this family undertaking in the 1950s, it had become a delicate job that Cai later named qi xian diao (lacquer thread sculpture).

The style requires piling and accumulating various diameters of lacquer threads on a lacquer-coated ware to form repeated patterns and complicated motifs of several levels. It can be done on a small porcelain vase or on large temple statues.

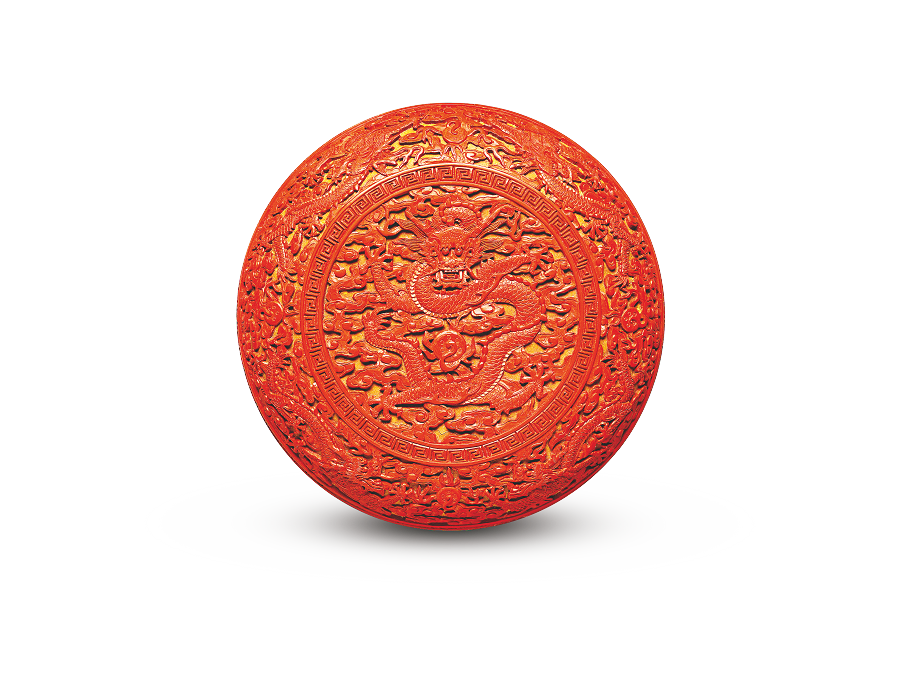

A lacquer box in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York features the motif of dragons and dates to the mid-18th century. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY

Both Gan and Cai have endeavored to keep the craft alive in modern life.

Gan has collaborated with luxury brands to integrate lacquerwork with new materials and designs. For example, he applied the xipi qi coating to part of a chair made of carbon fiber and a rosewood table to render “both classical and modern feelings”.

In the twilight of his life, Cai was devoted to cultivating the younger generation of lacquerers in his family while holding workshops and lectures at schools to popularize the craft. “It is my mission to inherit (the craft). It is my job to pass it on to the next generation, which is far more important than making money,” he once said.

Yang Peizhang from Tsinghua University says that aesthetics have evolved and will continue to transform, and however artistry is defined, the life of lacquerwork is first grounded on the well-preserved techniques passed down and based on artists developing new techniques to carry the tradition forward.

Lacquer art is widely applied in the making of various items, such as plates. PHOTO: CHINA DAILY