August 15, 2022

TOKYO — As Japan was running short of iron in the waning days of World War II, the military leadership looked for other materials to fashion grenades. One choice became the traditional Bizen pottery of Okayama Prefecture, and the master artisan of the day was ordered to make them.

Grenade shells made by Toshu Yamamoto (1906-94), who would be designated as a living national treasure as a ceramic artist, have been donated by his eldest son to the Okayama Prefectural Museum and the Bizen board of education ahead of the 77th anniversary of the end of the war on Aug. 15.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

Yuichi Yamamoto holds a Bizen hand grenade crafted during World War II by his father, in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture.

Yuichi Yamamoto, 86, hopes that the artifacts will convey a time in history in which the art of pottery — what should enhance life — was nearly used to destroy it as a weapon of war.

The donated grenade shells are about 8 centimeters high and 6 centimeters in diameter, and weigh between 240 and 270 grams.

Late in the war, the Japanese military ordered pottery makers throughout Japan to produce hand grenades as a substitute for iron. Yamamoto was among them.

“The sound of ‘bang! bang!’ still rings in my head,” Yuichi said, recalling the test firings of the grenades conducted near his home. “Shrapnel would be embedded deep in the wooden planks of the enclosure.”

The war ended before the Bizen hand grenades were actually used, which provides some relief for Yuichi, who is an official keeper of prefectural-designated important intangible cultural property.

“It is consoling that our pottery didn’t gain a history of harming people,” he said.

After the war, Yamamoto helped his father smash the grenades with a hammer. The fragments were buried along with whole grenades that did not break up.

Personnel from the U.S. Occupation Forces once came to ask about the explosives. But after being told that they had been disposed of, no action was taken against the family.

The Bizen hand grenades would not be seen again by human eyes until 1988. During a renovation of their house, several hundred were found in the ground. Toshu donated about 200 to the Bizen city government, saying, “This is what you get when art gets mixed up in war. It’s a terrible memory, but they have to be preserved.”

The Yomiuri Shimbun

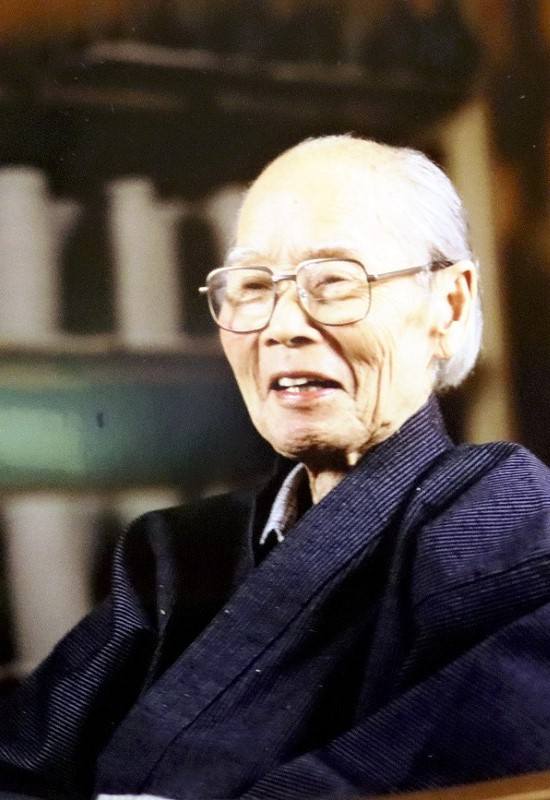

Toshu Yamamoto (1906-94)

After Toshu passed away in 1994, the grenades became largely forgotten. But in June this year, Yuichi was cleaning out his basement when he found the rest of the grenades.

Prior to his death, Toshu made his feelings about the grenades clear. “I do not recognize these as artwork. They cannot be sold,” he instructed.

Deeply concerned that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could provide a spark for another world war, Yuichi made the decision to donate the grenades with the idea they could play a role in teaching about peace.

On Aug. 2, he handed over about 400 hand grenades and 830 fragments to the Bizen city board of education.

The process gave him a chance to have a good look again at the grenades. Picking them up, he was amazed by the craftsmanship, of the near uniformity in size and thickness.

Most of the other ceramic grenades were said to have been made from dies, but he admired anew at his father’s skill with the potter’s wheel.

“Once war breaks out, even highly skilled artists will be used as fighting tools,” Yuichi said. “I hope we never again see a time come for such sorrowful pottery.”