September 23, 2024

SEOUL – Electric vehicle owners in South Korea’s crowded apartment complexes are beginning to feel like social outcasts.

“In my apartment, EV users are sometimes treated like criminals,” said Lee Ho-deok, an EV owner living in a large apartment complex in Seoul’s Mapo district, when describing the tense atmosphere.

In a city where over 85 percent of the population lives in multi-unit housing, apartment residents already contend with longstanding issues like noise between floors. But recently, EVs have become a new source of friction.

EVs versus neighbors

A Mercedes-Benz EV caused a major fire in the underground parking lot of a complex in Cheongna International City, Incheon, on Aug. 1. Since then, fears about the safety of EVs have swept Korea.

“Stories of parking bans and threats against EV owners have become common, such as in KakaoTalk chat groups among apartment EV owners, where residents vent their frustrations and anxieties,” Lee said.

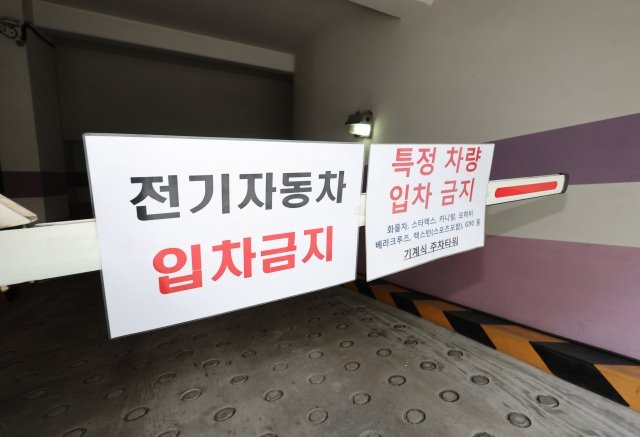

A sign blocks electric vehicles from accessing an underground parking facility in the Namdong district of Incheon, a prominent industrial and residential area. Incheon is a major metropolitan city located on the northwestern coast of South Korea, adjacent to the capital, Seoul. PHOTO: NEWSIS/THE KOREA HERALD

A survey by the Korea Electric Vehicle User Association found that more than half of the 3,000 apartment complexes surveyed had experienced disputes over EVs. Non-EV owners are pushing for extreme measures, such as banning EVs from underground spaces entirely, while EV owners feel they are being unfairly targeted by what they see as irrational fears.

Residents are taking matters into their own hands to ease fears about EV fires. An EV owner from an apartment complex in Seoul’s Gangseo district, who requested anonymity, contacted the local fire station and secured a commitment for EV fire drills at his apartment complex. The complex manager posted this information on public notice boards, which helped calm some concerns.

“Obviously, this doesn’t solve the fire risk, but it’s something. It ultimately feels like a battle between those who believe in EVs as the future and those who don’t want to deal with them,” he said.

Government’s push for smart-controlled EV chargers

To address these growing concerns, the Korean government introduced a comprehensive safety management plan for EVs on Sept. 6. Among several proposed measures — ranging from improved fire-fighting facilities in underground spaces to a new government battery certification system — the rollout of smart EV chargers has received the most attention. The government plans to install 20,000 of these chargers by 2024, increasing to 70,000 by 2025.

“We’re waiting for these smart chargers to be installed because, frankly, the situation with non-EV owners is getting unbearable. The Incheon fire didn’t even involve a car being charged, but if these chargers can help calm people down, we’ll take it,” said the EV owner in Gangseo.

A Level 2 charger equipped with a Power Line Communication module is being used to demonstrate overcharge protection and fire prevention measures, funded by a South Korean government initiative. PHOTO: NEWSIS/THE KOREA HERALD

Currently, South Korea has around 240,000 Level 2 EV chargers installed in apartment complexes, many of which lack smart-control technology. These new chargers aim to reduce fire risk by limiting charging levels and monitoring battery conditions in real time, offering what the government calls a “multi-layer” safety system alongside the vehicle’s onboard battery management system.

But will smart chargers actually reduce the chance of fires and calm public fears?

Smart-controlled chargers serve two key functions. First, they can limit the battery’s charge level, typically to around 80 to 90 percent to prevent overcharging. Second, they communicate with the vehicle to monitor battery health in real time. If the charger detects any anomalies, it can reduce the charging speed or shut down the process entirely to prevent an incident.

In theory, this system provides an extra layer of safety. However, the reality is more complicated.

The compatibility problem

For smart chargers to function as intended, both the charger and the EV must be equipped with Power Line Communication, a technology that allows them to “talk” to each other. The problem is that not all EVs are compatible with this technology.

While Hyundai-Kia and KG Mobility have pledged to make their battery data accessible to these chargers, no foreign automakers have followed suit. This means that many of the EVs currently in use may not be able to take advantage of these safety features anytime soon. Meanwhile, the selected EV charger providers will receive a 400,000 won ($300) subsidy for each PLC-equipped unit they install.

Furthermore, some automakers are skeptical of the benefits. A recent statement from Hyundai-Kia said overcharging was not a cause of EV fires: “From a user’s point of view, overcharging doesn’t really exist. Even when a battery is charged to 100 percent, it’s not actually 100 percent full. Most EV fires are caused by internal short circuits or external impacts, not by overcharging.”

The Korean government seems to agree — partially. During a press conference announcing the safety measures, Bang Ki-seon, the minister for government policy coordination, said, “Whether overcharging causes fires has indeed not been scientifically proven.” Still, he argued that smart chargers could serve as an additional safeguard, “checking for overcharging when the vehicle’s own systems fail.”

A layer of safety — or a band-aid?

Despite government assurances, experts remain divided on whether smart-controlled chargers will meaningfully reduce EV fire risks. Professor Han Se-kyung of Kyungpook National University, an expert in electrical engineering, likens the unpredictability of battery failures to human illness.

“Battery fires occur when lithium ions mutate during the charging process — similar to how cancer cells form. There are thousands of possible causes, and we can’t always identify the root issue. In the case of the recent Mercedes-Benz fire, for example, we still don’t know if the problem was with the battery cells supplied by Farasis Energy,” he said.

Han points out that EV battery safety is an extraordinarily complex issue, with potential problems occurring at multiple stages — from the initial manufacturing of the battery cells to their assembly into packs, and even during daily use. Given the complexity, it’s challenging to detect and prevent every possible fault that could lead to a fire.

“Detecting early signs of battery failure requires large datasets and sophisticated algorithms, something that would likely take a decade or more to develop reliably,” he added.