June 26, 2023

JAKARTA – Nothing lasts forever, and the corporate world is no exception. Losing a partner in a business venture is not the end. Many a firm has emerged from a breakup.

The question is how to gather the pieces and bounce back.

Chef and steakhouse owner Afit Dwi Purwanto is one of a relatively small group of people to open up about their business breakup, namely one he and his business partner Wynda Mardio experienced back in 2012.

After the split, Afit changed the logo and created new recipes that he kept hidden from his former business partner. His name now features on the new Holycow logo, with the tagline “Steakhouse by Chef Afit.”

Meanwhile, Wynda owns the Holycow Steak Hotel, the brand that existed before the split.

The changes were aimed at distinguishing Afit’s business from Wynda’s.

“We chose to expose this partnership split to inform our customers of this difference. So in the end, I altered [the brand] to enhance its value [with my personal touch],” Afit told The Jakarta Post in a phone interview on June 17.

Failure in business was never good news per se, Afit said, but what happened from that point on was entirely up to the owners: “This incident is indeed unpleasant, but it depends on how we deal with it.”

Agreements matter

The Holycow case is far from the only business split-up. Suharti’s fried chicken enterprise has thrived since its separation.

Suharti and her husband Bambang Sachlan Pratohardjo had opened their chicken diner in Jakarta in 1972, before opening more restaurants in the capital and expanding to Bandung and Bali, Tempo magazine reported.

However, after Suharti and her husband divorced in 1991, Bambang took over the family business, which still bears his ex-wife’s name, because he was the registered owner.

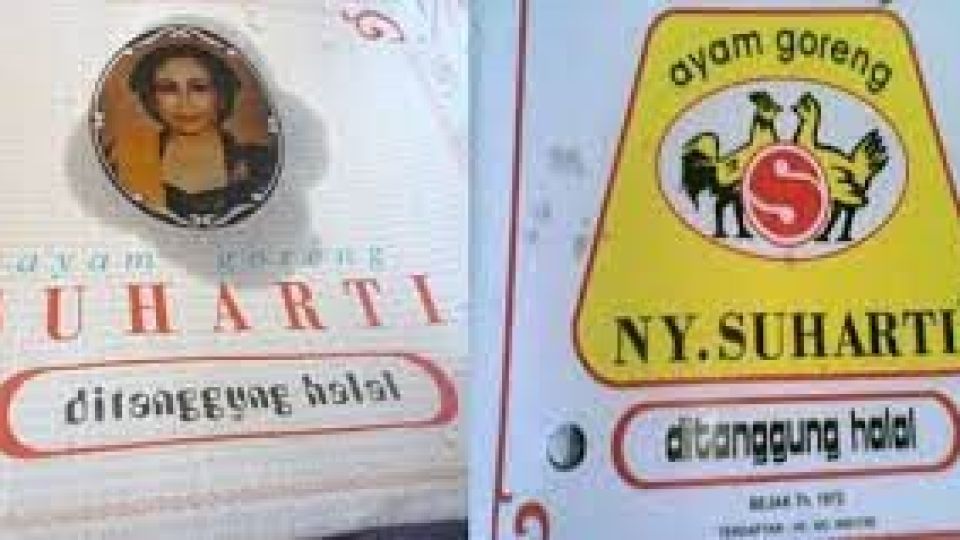

It was not until later that Suharti created her own brand, with a new logo. While Bambang now runs Ayam Goreng Ny Suharti, Suharti runs the similar-sounding Ayam Goreng Suharti.

Malvin Hariyanto, a Malang-based legal practitioner, said business owners must pay special attention to the details of split-up agreements.

Sometimes, both partners could retain their “identity” from their previous business, but often a mediator was required to handle disagreements between the stockholders, Malvin explained.

“For example, from my experience, there is one case where one party in a jointly owned grocery story did not stick to an agreement to purchase goods from a certain supplier. That party was obliged to pay Rp 1 billion (US$67,000) to the partner,” said Malvin, who works with the William & Malvin Law Office.

He added that that dispute need not have led to a partnership breakup, as there were other ways to resolve such situations.

Similar logos

Giovanni Christy, a Jakarta-based legal practitioner with Robin Sulaiman & Partners, noted the importance of agreeing on intellectual property rights.

“For example, in a restaurant, there is actually a brand that is listed, but then there is also such a thing as a trademark coexistence agreement,” she said, adding that this could prevent problems associated with similar names after a partnership breaks up.

“Intellectual property rights are necessary, such as when it comes to [determining who is] entitled to receive profit, for example, if someone wants to franchise a certain brand,” Giovanni noted.

“Otherwise, people will be confused about which side [gets the profit] if there are two founders.”

According to Law No. 20 of 2016 on trademarks and geographical indications, exclusive rights are provided to registered trademark owners for personal use. Trademark owners may authorize others to use their brand.

A trademark consists of a picture, a logo, a name, a word, a letter, a number and a color combination. Trademarks are available in 2D, 3D, holographic and audio formats. A trademark can be registered if it differs from existing registered trademarks. Trademark protection lasts for 10 years, but the owner has the option to prolong the protection.

“Business owners can easily file coexistence agreements. Unlike in the US, Indonesia has no specific statutes on such agreements, but business owners may reach a settlement. Coexistence can also be achieved by gentlemen’s agreement.”

She further explained that registration was not guaranteed as trademark examiners in Indonesia evaluated applications subjectively, without fixed regulations.

My customers, your customers

Wynda told the Post on June 16 that one of the most important things with business rebranding was to focus on the customers, because a brand’s ability to endure hinged on the depth of the owner’s connection with the target audience.

For example, even though Holycow Steak Hotel has a bigger name than a decade ago, Wynda still gets personally involved as much as possible, from creating new menus to marketing processes.

She added that she positioned her restaurant differently today than a decade ago, precisely to keep the same customers. “Our customers now have families, so they need a more comfortable place than before, when the restaurant was a warung (simple eatery).

“Because our customers grow, we as a brand must also grow. We can’t just lean back [and say] ‘this way is okay’,” said Wynda, explaining a key aspect of rebranding.

Septyan Pratama, a brand designer based in Bandung, said firms could successfully rebrand themselves when they already know their target audience.

“Splitting up a business can be a double-edged sword. You may get new chances. Firms that fail to rebrand usually have FOMO [fear of missing out] and don’t grasp their target market,” the 28-year-old said.

Make it your own

Afit seized the chance to make his brand more personal after the split by adding his name. He said he also allowed his customers to choose the new logo.

“So, at the time, I thought about how to differentiate [my brand] from the other one, so that people would know,” Afit said.

What Afit did is similar to Suharti’s rebranding. Even though Suharti had been running her business for decades, she had no legal say. Suharti later mustered the confidence to redesign and personalize the logo, even utilizing a photo of herself to create an identity for her now-famous fried chicken chain in October 1991, as reported by Liputan6.

Septyan explained that such personalization could help safeguard the connection with customers which would otherwise be jeopardized by the split. “Personalization creates a new touch, so that the impression can be different but the soul remains,” Septyan said.

Wynda opined that rebranding was not a must in a business breakup but should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

“If we just rebrand without clear objectives, it’s rather difficult. We should determine what the aim is, and then we have to do the market research,” Wynda closed.