November 5, 2024

ULAANBAATAR – The little-known Mongolia is increasingly coming into the public view. US Secretary of State Blinken was in Ulan Bator in August and proposed a third, virtual, border with the United States. Hopefully he did not have any more military bases in mind, because Mongolia is geostrategically centrally located between China, America’s “systemic rival” – as if competition were not good for business – and the alleged “evil empire”, Russia.

Putin was also in the country in September to renew the decades-long friendship from Soviet times and to conclude new agreements in the energy sector. The French President was there in May, because the numerous nuclear power plants in France require a lot of uranium, one of the many natural resources that Mongolia has in large quantities.

In West Africa, Macron had to put relations on hold following a coup in Niger, the previous supplier of uranium ore, because of accusations of neo-colonialism. And even the Pope was in Ulan Bator a year ago at the invitation of the government, for the first time in history, which had a very long prelude.

After the western campaigns of Genghis Khan and his successors in the first half of the 13th century, panic broke out in Europe. And after the sudden withdrawal of the Mongolian troops in 1241 because of Ögedei Khan’s death, papal emissaries were sent to the Mongolian court to assess the situation. In 1246, the Franciscan John de Plano Carpini attended the enthronement of Genghis Khan’s grandson Güyük near Karakorum and delivered two papal letters full of accusations about the campaigns against Christian Eastern Europe and demanding submission.

Of course, the new Khan rejected this request in a sharp tone. The French King Louis IX had another reason for contacting the Mongols. He was looking for allies for the Crusades against the Muslims in the Holy Land, who had brought Jerusalem under their control, and hoped, briefly even successfully, for a Mongolian military alliance.

Rock carvings in the Mongolian Altai from the Neolithic period

Mongolia is about four times the size of Germany and has a population the size of Berlin. The country is interesting not only because of its mineral resources and not only for geopolitical reasons, but also because of its little-known cultural treasures. In the Mongolian part of the Altai Mountains there are petroglyphs, rock carvings, dating from 11,000 years ago to around 800 years CE. They were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2011. The Mongolian Altai is located in the border region between China and Russia and is up to four thousand meters high, with numerous, deeply cut valleys running through it. The oldest of many thousands of rock carvings in Tsagaan Salaa document the imagination and life of the Stone Age society of hunters and gatherers in what was then a forested mountain range. In Tsagaan Gol you can find petroglyphs from a later era that document the transition to a nomadic society with livestock farming and horse breeding. They date from the Bronze and Iron Ages to the time of the Turkic peoples in the 8th century AD and are partly of excellent quality.

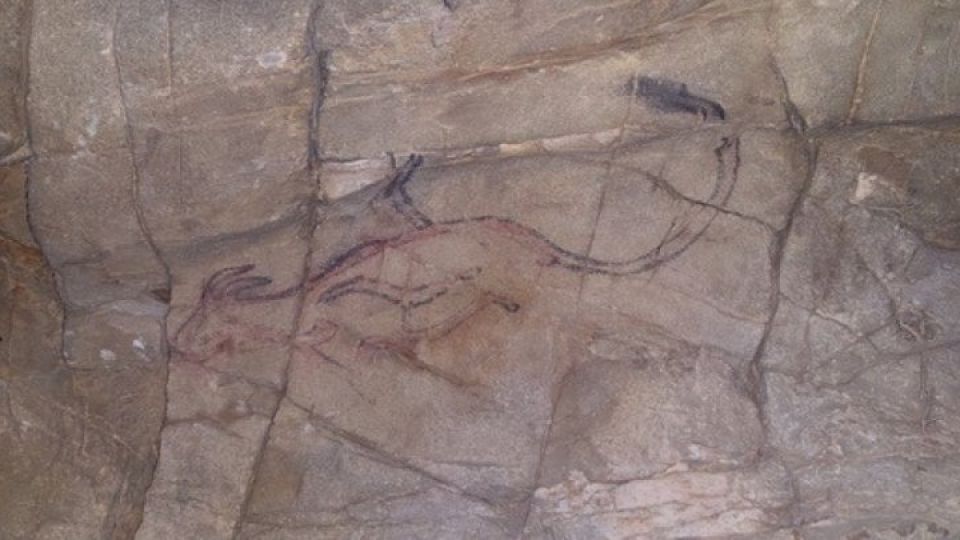

Cave paintings from the Paleolithic period

This year my life partner, who has her roots in Ulan Bator, and I were once again traveling in the Altai Mountains. We knew from an English travel guide that there are also cave paintings from the Paleolithic period in the Altai region and we took a trip with our guide Jagaa from “Explore the Great Altai” to the Tsenkher Caves, about ninety kilometers south of the district capital Khovd. And indeed, they exist! The main cave is unguarded, hardly developed for tourism and you have to climb into small side caves with good shoes to be able to see the treasures. They are less spectacular than their French or Spanish counterparts, smaller and less colorful, but their existence alone is a sensation, so little known. The caves were discovered in 1951 by the Mongolian geologist Namnandorj, then explored by a Russian-Mongolian expedition in 1967 and declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. You can see antelopes, lions, ostriches, mammoths, camels and cranes. The images were partly sketched with flint and painted with reddish-brown ochre on a yellowish-white background.

According to official information, the dates so far range from 15,000 to 40,000 years old. Perhaps they should be updated at some point using the uranium-thorium method. For comparison: The famous rock paintings in the French cave of Lascaux are around 17,000 years old, while those on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi are over 40,000 years old. Very close to the caves we were also able to observe the very rare Mongolian saiga antelopes, which were severely decimated by an epidemic in 2017 and 2018, followed by an extremely harsh winter. We all thought about how little the caves in the Altai have been explored so far and how much there is still to discover here. The whole area was inhabited by human beings for tens of thousands of years.

On the Russian side of the Altai Mountains, archaeologists from the Russian Academy of Sciences, Anatoli Derevianko and Michael Shunkov, discovered a fragment of a girl’s finger bone in 2008. Two years later, following a DNA analysis at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig under the direction of Svante Pääbo, it was possible to assign it to a new, long-extinct human species, the Denisovans, an Asian cousin of the Neanderthals. It would not be surprising if such finds were made on the Mongolian side as well, and another chapter could be added to the history of the origins of man. International cooperation could be very valuable here and send a positive signal in turbulent times and a dangerous global situation.

Mongolia behaves wisely, neutrally and confidently

Meanwhile, Mongolia behaves neutrally between the two centers of power on its northern and southern borders. The country belongs neither to the BRICS states nor to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Its small, multi-ethnic, multilingual and tolerant population is increasingly asserting itself confidently and proudly on the world stage. On our return journey back to Berlin, we wondered whether the leadership of our eastern neighbor in Europe, Ukraine, could not have prevented the war, which is also a proxy war, with such a basic attitude – model Switzerland or model Mongolia, as you like.

Peter Gorenflos is a surgeon in Berlin and, among other things, editor of the Mongolian edition of Karlheinz Deschner’s “God and the Fascists”

by Peter Gorenflos, Berlin, October 2, 2024

The little-known Mongolia is increasingly coming into the public view. US Secretary of State Blinken was in Ulan Bator in August and proposed a third, virtual, border with the United States. Hopefully he did not have any more military bases in mind, because Mongolia is geostrategically centrally located between China, America’s “systemic rival” – as if competition were not good for business – and the alleged “evil empire”, Russia. Putin was also in the country in September to renew the decades-long friendship from Soviet times and to conclude new agreements in the energy sector. The French President was there in May, because the numerous nuclear power plants in France require a lot of uranium, one of the many natural resources that Mongolia has in large quantities. In West Africa, Macron had to put relations on hold following a coup in Niger, the previous supplier of uranium ore, because of accusations of neo-colonialism. And even the Pope was in Ulan Bator a year ago at the invitation of the government, for the first time in history, which had a very long prelude.

After the western campaigns of Genghis Khan and his successors in the first half of the 13th century, panic broke out in Europe. And after the sudden withdrawal of the Mongolian troops in 1241 because of Ögedei Khan’s death, papal emissaries were sent to the Mongolian court to assess the situation. In 1246, the Franciscan John de Plano Carpini attended the enthronement of Genghis Khan’s grandson Güyük near Karakorum and delivered two papal letters full of accusations about the campaigns against Christian Eastern Europe and demanding submission. Of course, the new Khan rejected this request in a sharp tone. The French King Louis IX had another reason for contacting the Mongols. He was looking for allies for the Crusades against the Muslims in the Holy Land, who had brought Jerusalem under their control, and hoped, briefly even successfully, for a Mongolian military alliance.

Rock carvings in the Mongolian Altai from the Neolithic period

Mongolia is about four times the size of Germany and has a population the size of Berlin. The country is interesting not only because of its mineral resources and not only for geopolitical reasons, but also because of its little-known cultural treasures. In the Mongolian part of the Altai Mountains there are petroglyphs, rock carvings, dating from 11,000 years ago to around 800 years CE. They were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2011. The Mongolian Altai is located in the border region between China and Russia and is up to four thousand meters high, with numerous, deeply cut valleys running through it. The oldest of many thousands of rock carvings in Tsagaan Salaa document the imagination and life of the Stone Age society of hunters and gatherers in what was then a forested mountain range. In Tsagaan Gol you can find petroglyphs from a later era that document the transition to a nomadic society with livestock farming and horse breeding. They date from the Bronze and Iron Ages to the time of the Turkic peoples in the 8th century AD and are partly of excellent quality.

Cave paintings from the Paleolithic period

This year my life partner, who has her roots in Ulan Bator, and I were once again traveling in the Altai Mountains. We knew from an English travel guide that there are also cave paintings from the Paleolithic period in the Altai region and we took a trip with our guide Jagaa from “Explore the Great Altai” to the Tsenkher Caves, about ninety kilometers south of the district capital Khovd. And indeed, they exist! The main cave is unguarded, hardly developed for tourism and you have to climb into small side caves with good shoes to be able to see the treasures. They are less spectacular than their French or Spanish counterparts, smaller and less colorful, but their existence alone is a sensation, so little known. The caves were discovered in 1951 by the Mongolian geologist Namnandorj, then explored by a Russian-Mongolian expedition in 1967 and declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. You can see antelopes, lions, ostriches, mammoths, camels and cranes. The images were partly sketched with flint and painted with reddish-brown ochre on a yellowish-white background.

According to official information, the dates so far range from 15,000 to 40,000 years old. Perhaps they should be updated at some point using the uranium-thorium method. For comparison: The famous rock paintings in the French cave of Lascaux are around 17,000 years old, while those on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi are over 40,000 years old. Very close to the caves we were also able to observe the very rare Mongolian saiga antelopes, which were severely decimated by an epidemic in 2017 and 2018, followed by an extremely harsh winter. We all thought about how little the caves in the Altai have been explored so far and how much there is still to discover here. The whole area was inhabited by human beings for tens of thousands of years.

On the Russian side of the Altai Mountains, archaeologists from the Russian Academy of Sciences, Anatoli Derevianko and Michael Shunkov, discovered a fragment of a girl’s finger bone in 2008. Two years later, following a DNA analysis at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig under the direction of Svante Pääbo, it was possible to assign it to a new, long-extinct human species, the Denisovans, an Asian cousin of the Neanderthals. It would not be surprising if such finds were made on the Mongolian side as well, and another chapter could be added to the history of the origins of man. International cooperation could be very valuable here and send a positive signal in turbulent times and a dangerous global situation.

Mongolia behaves wisely, neutrally and confidently

Meanwhile, Mongolia behaves neutrally between the two centers of power on its northern and southern borders. The country belongs neither to the BRICS states nor to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Its small, multi-ethnic, multilingual and tolerant population is increasingly asserting itself confidently and proudly on the world stage. On our return journey back to Berlin, we wondered whether the leadership of our eastern neighbor in Europe, Ukraine, could not have prevented the war, which is also a proxy war, with such a basic attitude – model Switzerland or model Mongolia, as you like.

Peter Gorenflos is a surgeon in Berlin and, among other things, editor of the Mongolian edition of Karlheinz Deschner’s “God and the Fascists”