May 20, 2024

MORIOKA – A unique postbox that receives letters with messages for people who died in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake stands on the Hirota Peninsula in Rikuzen-Takata, Iwate Prefecture.

A man who has operated the postbox once thought about closing it because he had to take care of his mother. However, when he saw people who had lost their family members due to the Noto Peninsula Earthquake, he changed his mind.

“I thought that there is still a role for the postbox,” he said.

This spring, a temple on the peninsula took over the postbox from the man so that it could continue to serve the people affected by the disaster.

The postbox was set up in 2014 by Yuji Akagawa, 74. Seeing people affected by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami who were unable to talk about their feelings of sadness and despair, he wanted them to feel a sense of peace by writing letters to their family members or friends who had died in the disaster.

Akagawa named the postbox “Drifting 3.11 Postbox” as it is the place where letters with nowhere to go would end up drifting. He managed the postbox while running a cafe at the tip of the peninsula.

So far, the postbox has received more than 1,000 letters saying such things as: “I wish I could meet you in my dreams” and “I always think of you.”

Setsuko Sato, 68, of Sendai, who lost her 56-year-old firefighter husband in the tsunami in Minami-Sanriku, Miyagi Prefecture, has been emotionally supported through the postbox.

“You will always be 56 years old, and my age has surpassed yours. I want to see you,” she wrote in a letter after dreaming of her husband three years after the Great East Japan Earthquake. In the letter, she wrote her feelings that she had kept to herself. When she sent the letter, her heart felt lighter because she was able to express feelings that she could not express even to her son or brothers. Since then, she has been writing letters whenever she feels like it, sending one or two letters a year.

While Akagawa continued to manage the postbox, he had to start taking care of his 98-year-old mother, who was beginning to show symptoms of dementia. He began to consider closing the postbox around 2022.

Amid such circumstances, the situation in the areas hit by the Jan. 1 Noto Peninsula Earthquake reminded Akagawa of the situation immediately after the 2011 disaster.

“I thought that many people in the Noto region must have sad feelings that they cannot express to those around them,” he said.

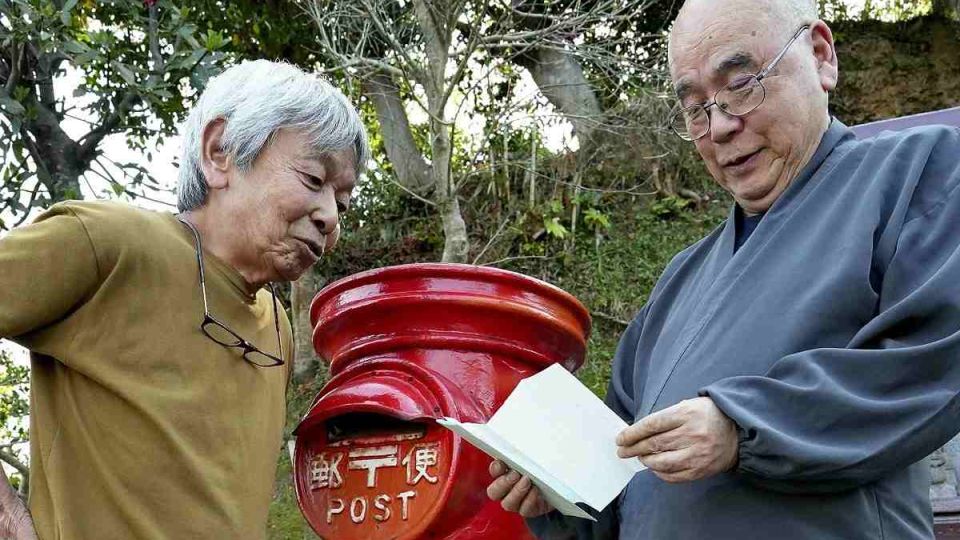

Akagawa asked the Jionji temple in the city, which he had asked to hold memorial services for the letters, to take over the postbox. Keiko Furuyama, 75, a former priest of the temple, accepted the request.

“This is the role that temples should perform. I would like to listen to the feelings of the people affected by the disaster as much as possible,” Furuyama said. The postbox was moved to the temple grounds at the end of March, and he began accepting letters in April.

“I am relieved that I could find a new custodian of the postbox,” Akagawa said.

Thirteen years after the Great East Japan Earthquake, many of the letters are about the daily events of bereaved families.

“I don’t want my husband to worry about me forever. I want to write letters that make him think I’m enjoying my life,” Sato said.